“Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass” acquired by the University

Rediscovered song honoring Frederick Douglass to be performed for the first time in a century

In 1847 Frederick Douglass was getting ready to leave England where he had lived to avoid being recaptured after his escape from enslavement in Maryland. He had crisscrossed Britain for the last 19 months, lecturing on the evils of slavery in his native country. Now that supporters had raised 150 English pounds (about $750 then) to buy his legal freedom, he was able to return to his family in the United States. Yet, his safe passage was by no means guaranteed.

To commemorate Douglass’s departure from Britain, his close companion and fellow abolitionist, the Englishwoman Julia Griffiths, wrote the “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass.” Only two copies of the sheet music are known to exist—and one of them was acquired earlier this year by the University of Rochester’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation. In early December, the song was performed as part of this year’s celebrations to mark the bicentennial of the birth of the renowned publisher, orator, freedom fighter, and statesman.

David Blight, the Class of 1954 Professor of American History at Yale University and the author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (Simon & Schuster, 2018) delivered the keynote lecture as part of the event.

In 1847 when Douglass first arrived in Rochester, he found a bustling city of 50,000. It was here that same year that he launched his abolitionist newspaper the North Star. “The paper was to be a proud black enterprise,” writes Blight in his new biography.

It was also in Rochester that Douglass gave his most famous speech, “What to the Slave is the 4th of July,” at the majestic Corinthian Hall in 1852. “What Douglass crafted and delivered… was nothing less than the rhetorical masterpiece of American abolitionism,” writes Blight.

Over the last few decades, the University has assembled one of the world’s leading archival collections of rare Douglass materials, including letters, published speeches, Underground Railroad passes that had been used to smuggle slaves to safety, and other ephemera that document and expand upon Douglass’s history and activity. The collection is part of a larger repository of materials documenting the history of abolition and woman suffrage movements.

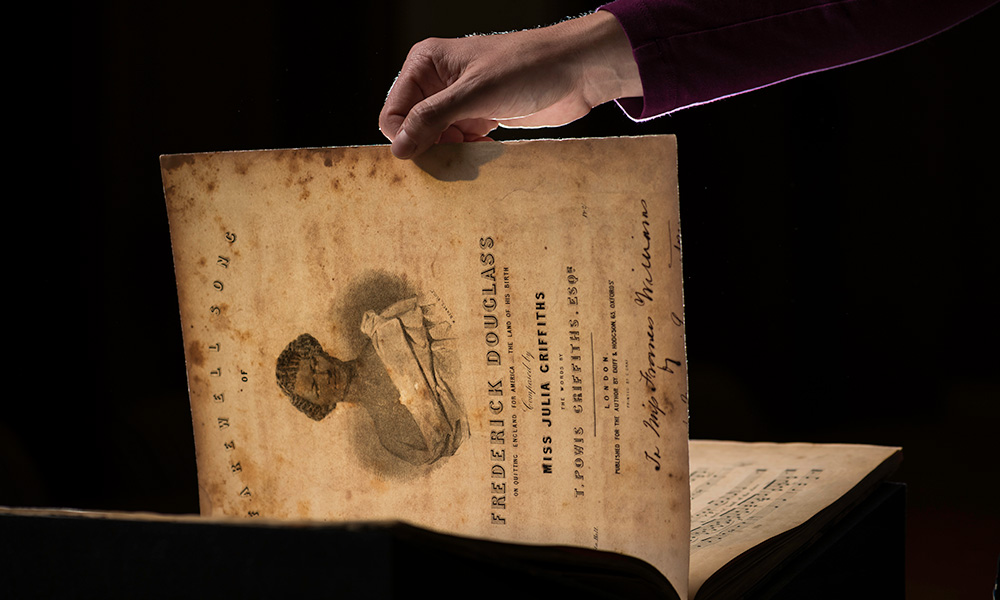

Autumn Haag, the University’s special collections librarian and archivist for research and collections, holds the title page of “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass,” composed by Julia Griffiths and contained within a volume of sheet music recently purchased at auction by the University of Rochester Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation. The piece is believed to be the only one of its kind in the United States.

(University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

Only copy in the United States

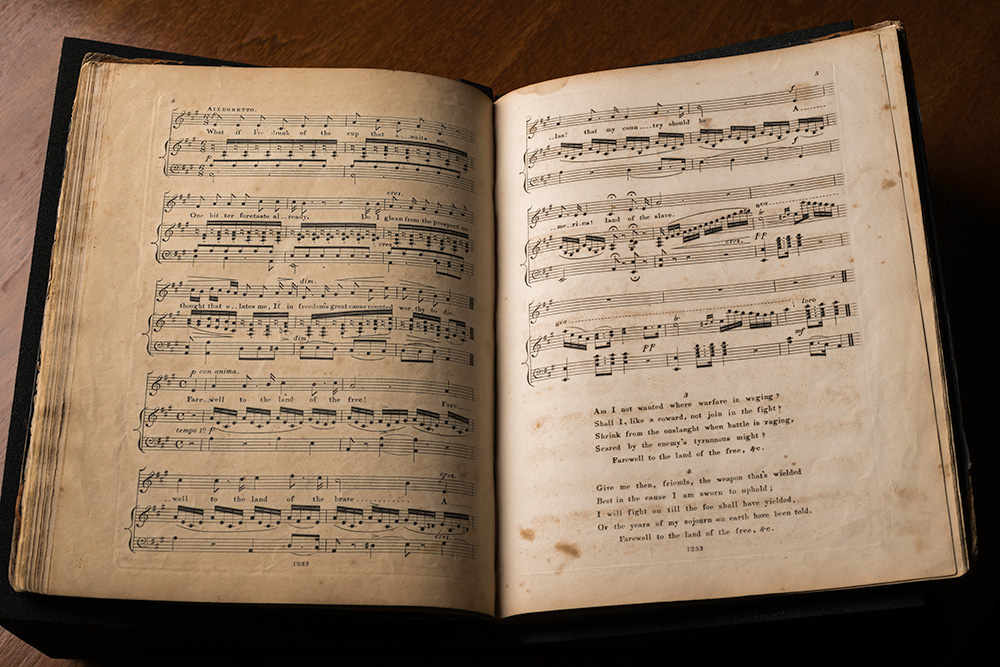

The copy of Griffiths’s song now owned by the University is tucked inside a well-worn, black cloth book including 16 bound pieces of sheet music. Now referred to as the Francis A. Williams songbook, it bears the name of its former owner stamped in gold lettering on its cover. “Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass” is scored for voice and piano. Griffiths’s brother, the lawyer T. Powis Griffiths, penned the lyrics.

Having one’s own sheet music bound was not uncommon in the 19th century, says Autumn Haag, the University’s special collections librarian and archivist for research and collections.

What makes this book so valuable is the rarity of the Douglass song. The only other known copy resides at the British Library in London.

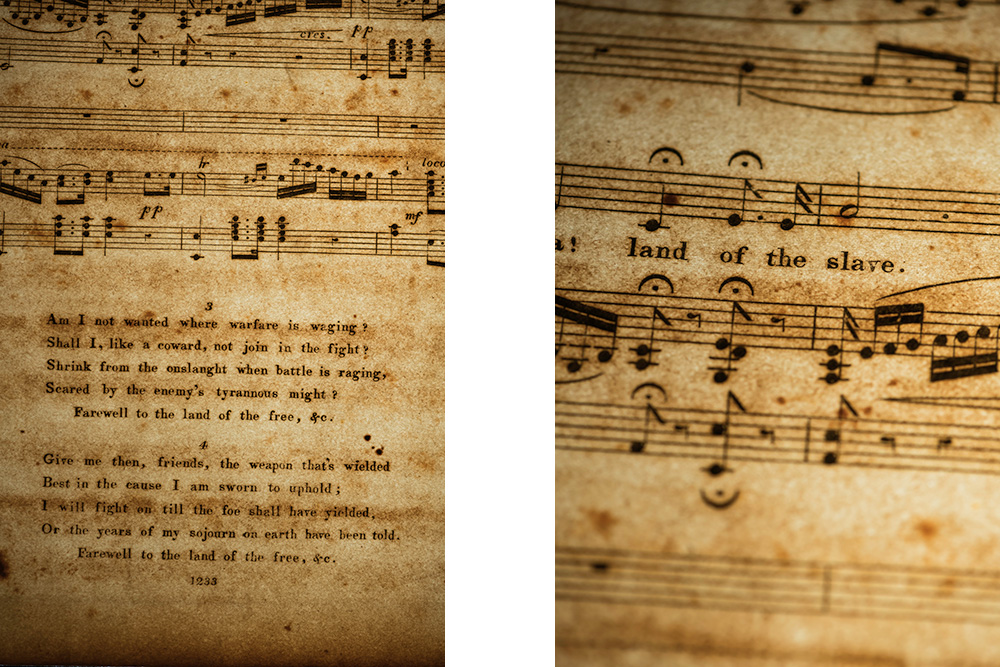

Subtitled “On Quitting England for America — the Land of His Birth,” the song decries the United States as a brutish country. England is styled as the “land of the free, the land of the brave” while the lyrics lament “Alas! that my country should be America! land of the slave.”

The Griffiths imagine the song from Douglass’s perspective, concluding that the abolitionist leader needs to return to America and join the fight against slavery, even if it could spell his death.

“Shall I, like a coward, not join the fight? Shrink from the onslaught when battle is raging, Scared by the enemy’s tyrannous might? […] I will fight on till the foe shall have yielded, Or the years of my sojourn on earth have been told,” wrote lawyer Griffiths in Douglass’s imaginary voice.

Haag says she is struck by the use of martial imagery and words like “warfare,” “battle,” and “weapon,” especially in the last two verses. “It feels like the lyrics are already foreshadowing the Civil War,” which was to break out 14 years later.

READ THE LYRICS: Farewell Song of Frederick Douglass On Quitting England for America—the Land of his Birth

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave.1 What if the Negroes despis’d and degraded

And scorn and reproach are heap’d on his head

Perish the thought that would leave him unaided

American soil shall be that which I tread.

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

2 What if I’ve drunk of the cup that awaits me,

One bitter foretaste already,

Do I glean from the prospect no thought that elates me,

If in freedom’s great cause counted worthy to die.

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

3 Am I not wanted where warfare is waging?

Shall I, like a coward, not join the fight?

Shrink from the onslaught when battle is raging,

Scared by the enemy’s tyrannous might?

Farewell to the land of the free! Farewell to the land of the brave. Alas! That my country should be America! Land of the slave. [repeat]

4 Give me then, friends, the weapon that’s wielded

Best in the cause I am sworn to uphold;

I will fight on till the foe shall have yielded,

Or the years of my sojourn on earth have been told.

Farewell to the land of the free, etc.

The book’s title page shows a stylized image of Douglass, wearing a classical-style toga artfully draped over his left shoulder, meant as an allusion to ancient Greece or Rome. The image, depicting Douglass with a stoic look, sharp jawline, and a bit of a Roman nose, is not a true representation of the man, says Haag.

Was it propaganda? she muses. “Propaganda has sometimes negative connotations, but yes. It was written for a purpose.” It was written to remind Douglass’s supporters in England what he was returning home to, and to highlight to abolitionists in the United States the essential difference between the two countries at the time, says Haag.

How did the rare sheet music end up in America?

Haag has worked to piece together how the book ended up on this side of the Atlantic. In the back of the bound volume, she discovered a newspaper clipping of music, cut out from a Cincinnati newspaper—enough for Haag to start a genealogical search for its previous owner, a Francis A. Williams in Ohio.

Soon she discovered that Williams was biracial, and one of the first women to graduate from Oberlin College, where she had studied music. She married a Peter H. Clark, one of Ohio’s most effective black abolitionist writers and speakers.

At this point, the songbook’s provenance and the song’s subject begin to intertwine: in 1853 Douglass appointed Clark secretary of the National Convention of Colored Men. Three years later, the Clarks moved to Rochester and took up residence in the Douglass home with their infant daughter, while Clark worked as an assistant on the Frederick Douglass’ Paper (formerly the North Star). Barely a year later, the young family moved back to Cincinnati where Clark found other employment.

“It’s very possible that Francis brought the book along with her to Rochester,” says Haag. “While we don’t know if she performed the song at the Douglass home, we know that Frederick Douglass played the violin and loved music.”

Of course, there’s also a chance that the song’s English author, who seven years earlier had also lived in the Douglass home, had brought another copy. Either way, Haag says, “we feel pretty certain that the music was in Rochester before and we’re bringing it now full circle.”

Acquiring the rare sheet music and continually seeking out other historic Douglass materials, “illustrates the University’s commitment to Frederick Douglass’s history and legacy,” notes Jessica Lacher-Feldman, the University’s assistant dean and the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation. “This is part of our stewardship of one of the most significant collections of Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony materials that help us understand the political, social, and cultural history of the abolition and women’s suffrage movements. Rochester was an epicenter for these important movements in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s this legacy that connects Rochester and human rights to this day.”

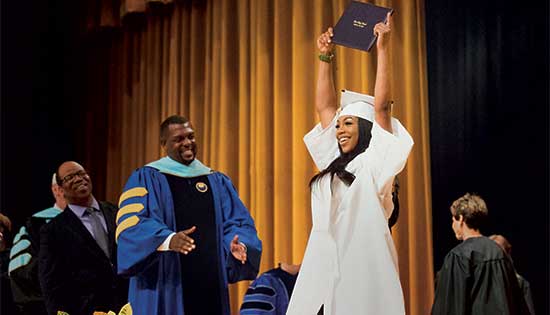

The song was performed live on December 3 at 7 pm at the Hochstein Performance Hall in coproduction with Rochester Institute of Technology as part of the festivities honoring Douglass’s bicentennial. The event, titled Prophet of Freedom: Honoring Frederick Douglass in Word and Song, will include a lecture with renowned Yale historian Blight.

It’s not just any musical performance, says librarian Haag: “with just two surviving copies, the music probably hasn’t been played in the last 100 years.”

Questions raised in Rochester and beyond

Blight consulted the University’s Douglass collections when he researched his book—some 10 years in the making. Referring to the sheet music and its composer, Julia Griffiths, he writes:

“Griffiths was no mere starry-eyed devotee. She was a manager of business affairs, as well as of people. She was a voracious reader and learner, her devotion to radical abolitionism provided what the movement often desperately needed—astute organization, financial foundation, and an apparently pure commitment to help Douglass go out and be Douglass.”

Incidentally, it was her relationship with Douglass that caused a scandal in Rochester and well beyond. Griffiths, a white Englishwoman, had followed Douglass—a married man with five children—to America in 1849 to become his confidante, business manager, fundraiser, and assistant editor of the North Star. Seven years his senior, she even lived for a while in the Douglass household, together with her sister Eliza.

Rumors circulated that their relationship had become intimate. At one point, Douglass and the Griffiths sisters were attacked in Battery Park at the lower tip of Manhattan, with one attacker’s hitting Douglass in the face.

Blight isn’t sure of the rumors’ veracity.

“This extraordinary and ultimately untenable situation of an educated white Englishwoman living in the Douglass home and laboring daily with him on his life’s work, while Anna Douglass raised five children in its midst, leads us to wonder whether the relationship was ever sexual,” writes Blight. “We do not know for sure, and perhaps, it does not matter.”

Douglass, for his part, turned the physical attack in Manhattan into an incisive analysis of racism. In his editorials, he sharply maintained the right to associate with anyone in public, including white female friends, calling his attackers the “bloodhounds of American slavery.”

Fast forward to today: the Douglass lecture in December took place in the same venue as his funeral in 1895 (Hochstein Hall was then Central Presbyterian Church). December 3 was also the same date on which Douglass published the first edition of the North Star with coeditor M.R. Delaney in 1847.

The two men wrote 171 years ago that it had long been their “anxious wish to see, in this slave-holding, slave-trading, and negro-hating land, a printing-press and paper, permanently established, under the complete control and direction of the immediate victims of slavery and oppression.”

In time, the publication would become the most influential black, antislavery paper of the antebellum period.