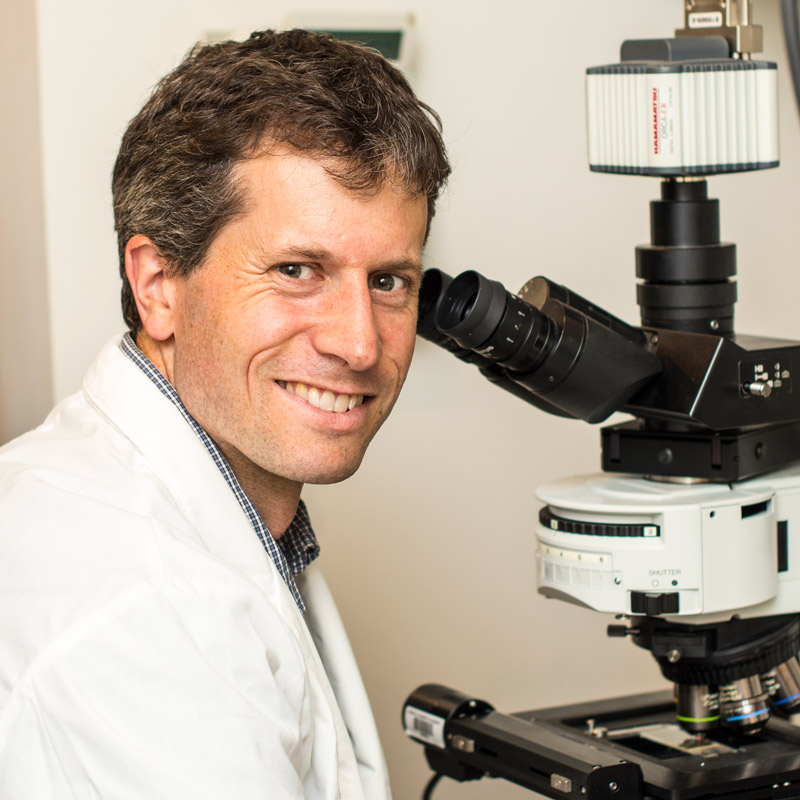

Working to slow or stop cognitive decline in MS patients

Working to slow or stop cognitive decline in MS Patients

“She said she’d gladly trade her walking for a wheelchair if it meant she could have her mind back.” — Matthew Bellizzi, MD, PhD

“She said she’d gladly trade her walking for a wheelchair if it meant she could have her mind back.” — Matthew Bellizzi, MD, PhD

For people with MS, a decline in cognitive function—such as memory, concentration, and planning and prioritizing—can often be the worst part of the disease. More than half of all people with MS will develop cognitive changes, which can become so severe that individuals can no longer function independently. Matthew Bellizzi, MD, PhD Assistant Professor of Neurology, hopes to slow or stop cognitive decline.

Dr. Bellizzi got into MS research in large part because of a patient he had back when he was a resident. “She was a lawyer with MS, and to look at her she seemed absolutely fine,” he says.

The lawyer could move, walk, and talk smoothly, but she had begun losing her ability to concentrate, had to prepare hours for a meeting, and if the subject changed, she couldn’t adapt. “She was in her late forties and was going to have to quit her career. She said she’d gladly trade her walking for a wheelchair if it meant she could have her mind back,” Dr. Bellizzi says.

For decades, most MS research focused on one aspect of the disease: the degradation of the myelin sheath around neurons. This sheath acts like insulation around a wire, allowing electricity to flow properly through the neuron. One of the key symptoms of the disease is when lymphocytes, part of the body’s immune system, begin destroying the myelin, hampering the normal flow of signals through the neuron. The most obvious effects are a patient’s trouble controlling their movements, such as walking.

However, Dr. Bellizzi’s patient could walk without difficulty. She was suffering more from a second effect of the disease where the neurons themselves—the wires in the insulation—become damaged, which more often affects cognitive abilities. Researchers have made significant strides in mitigating the attack on the myelin sheath, but there has been very little progress understanding why neurons also degrade.

“When we look at a patient’s MRI we see lesions in the brain where the myelin has been attacked,” says Dr. Bellizzi, “But we also see neuron degradation happening throughout the brain, not just near the lesions. Though we’ve found ways to slow the attack on the myelin, the progression of damage to those neurons is not slowed in the same way. Our research is to find out why and how to save those neurons.”

Dr. Bellizzi believes brain-specific immune cells—microglia—become overactivated in MS patients. Instead of protecting nerve cells (called neurons), microglia produce by-products that ultimately harm them. These overactive immune cells spread throughout the brain, causing damage far from the myelin lesions. Treatments aimed at protecting the myelin may be doing only half the job.

“We’re investigating a way to control the brain’s immune response just enough to let it protect its neurons, but not so much it causes damage,” says Dr. Bellizzi. “It’s a balancing act, like taking ibuprofen to ease swelling when you twist your ankle—a little inflammation gets blood to the area to help heal it, but you don’t want your ankle to swell up so much it hurts. We need to find out exactly where that fine line is in MS. If we can do that, we might be able to slow or stop the cognitive decline that can often be the worst part of the disease.”

You can help

To learn how you can support multiple sclerosis research and care, contact James O’Brien, Senior Director of Advancement, Neuroscience, at (585) 276-6877.

—University of Rochester Medical Center Advancement Communications, May 2018