Looking at urban history as a fight for space, power

Chicago, Istanbul, Rome, and Delhi. The students in the 100-level course The City: Contested Spaces take a virtual tour of them all, while pondering an overarching question—can people’s lives be reshaped by redesigning urban spaces?

A model of interdisciplinary learning and collaborative teaching, the course at the University of Rochester has been taught twice now by historian Laura Smoller, anthropologist Llerena Searle, and art historian Peter Christensen.

“There’s a lot of activity crammed into small space,” assistant professor of anthropology Llerena Searle tells the students in a lecture on Delhi, above. The students were participating in this fall’s course on “The City: Contested Spaces,” an interdisciplinary first-year class taught by three professors from three different fields who explore how city dwellings and spaces fulfill different roles. (Getty Images photo)

Its origins are serendipitous. “We all arrived at Rochester at the same time—in the summer of 2014,” recalls Smoller, a professor of history and specialist in medieval and Renaissance Europe who taught previously at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. At the new faculty orientation, the trio quickly realized they were the only humanists in the room. They started talking and found they had things in common, including an appreciation of the classic work in American urban history, The Crabgrass Frontier, by Kenneth Jackson.

“It’s one of our favorite books,” Smoller and Searle, an assistant professor of anthropology, agree. Ditto, says Christensen, an assistant professor of art history. “We all had it on our bookshelves.”

They took that as a sign.

Regular lunch dates at the faculty club followed. During one of those lunches, Smoller talked about an interdisciplinary course she’d planned to teach at Arkansas. Christensen—whose research on architectural and environmental history spans Germany, Central Europe, the Middle East as well as nearby Buffalo—and Searle, whose work on the intersection of capitalism and urbanization in the developing world took her to India—listened intently. A plan for a collaborative course began to take shape. Soon all three were throwing out names of cities and possible themes. “A humongous laundry list,” Smoller laughs.

Ultimately, they realized it didn’t really matter which cities they chose, as long as there were plenty of “palimpsestic” examples to show—appropriated and reassigned spaces, gleaned and borrowed, partially erased and rebuilt, over and over. This multifaceted layering—the product of the interactions of city dwellers, architects, political leaders, and others over time—is a central feature of cities, the professors argue. And how that layering develops and shapes peoples’ lives is the principal subject of the course.

From left, Yaal Dryer ’20, Marcus Sim ’21, Samantha Turley ’18 (T5), Isabel Lieberman ’21, Tyler Stiggers ’21, and Warm Ayanaputra ’21, look at materials from the University’s archives related to their course on “The City: Contested Spaces.” (University photo / J. Adam Fenster)

The architecture of power

“There’s a lot of activity crammed into small space,” Searle tells the students in a lecture on Delhi. From rickshaw-jammed streets and the tangled maze of electricity wires, dangling seemingly willy-nilly between buildings and across narrow streets, to residences and street vendors crammed into the tiniest crevices—large swaths of Delhi barely leave space to navigate.

Next, she juxtaposes on the smartboard historical images of Delhi’s former Viceroy of India’s palace. “A space of imperial power,” she says, pointing to the generous layout of the surrounding greens and the wide, straight boulevard leading up the hill towards the imposing building. The construction of the Viceroy’s House, as the British called it, required the seizure and acquisition of 4,000 acres of land, forcing the relocation of 300 families.

Today, in an ironic twist of history, the building, renamed Rashtrapati Bhavan, is the official home of India’s president. “The space has been reappropriated and repurposed by the Indian people. Now, the open greens are used, especially on hot days, as a park for family picnics, to cool off and hang out,” says Searle, who lived in Delhi for 17 months.

Power—how space is used to produce or maintain a ruling grip—is a central theme of the course.

“It’s not about retaining encyclopedic knowledge,” says Christensen. “We want our students to develop critical thinking skills. Each lecture is a vignette of a particular moment in time, not a comprehensive study of one city.”

The professors sit in on each other’s lectures to guarantee seamless transitions with overarching themes, across their respective academic fields.

“We’re not splitting the responsibilities into thirds. It’s not a way of cutting corners,” Christensen adds with a smile.

It’s not just a tour de force for the students. “It’s so rare that we get to see another professor lecture,” says Searle. “To see two other faculty members practice their craft, to get to do discussion sessions together has been really great for picking up ideas.”

Smoller agrees. “From a selfish point of view, it’s a way to learn pedagogical techniques from my colleagues.”

The palimpsest of Rochester

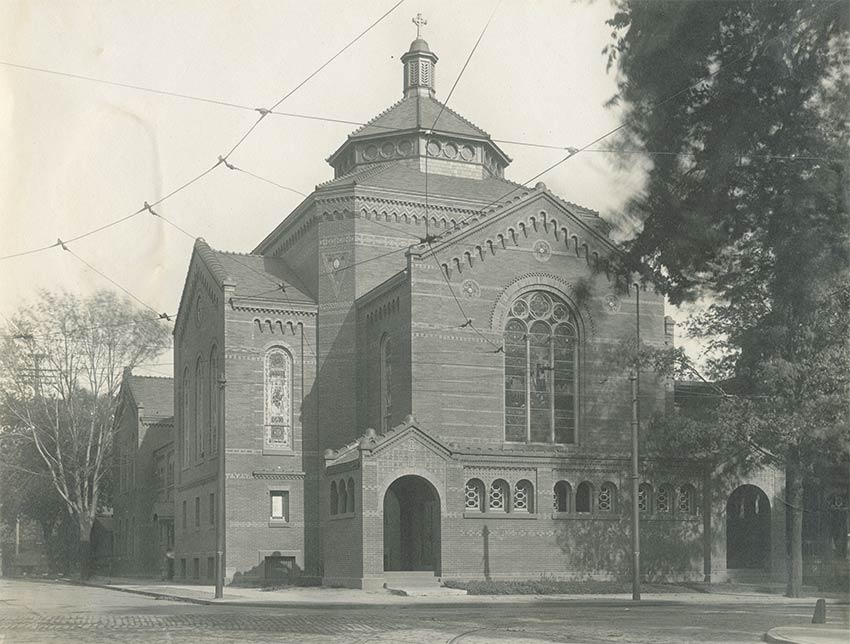

Part of the course work is hands-on and local: students apply lessons learned from the four big-city approaches to concrete examples closer to home—three distinct sites in the City of Rochester: Kodak Park, College Town, and the First Universalist Church on Clinton Avenue. In the latter example, the learning comes full circle: the church, dedicated in 1908, is a mix of architectural styles and epochs.

“There are several historical styles you can see here,” explains Mimi Cheng, a graduate student in visual and cultural studies who served as teaching assistant and discussion group co-leader last semester. “Clearly, influences of Gothic churches as well as some stylistic allusions to Byzantine and Roman architecture.”

The church’s architect, the late Claude Fayette Bragdon, incorporated a mix of Lombard Romanesque and American Arts and Crafts style elements.

“Bragdon was a very spiritual person, almost mystic, an American esoteric in a way,” says Christensen, also a trained architect. “He inflected the mainstream Arts and Crafts movement with a more austere mysticism. That’s what we see in his architecture.”

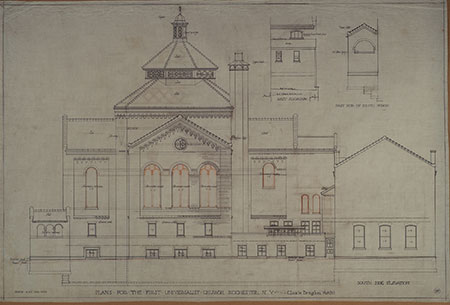

The original building plans for the First Universalist Church are now housed at the University’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation. Hunched over them some 110 years later is Yaal Dryer ’20, an ecology and evolutionary biology major (with a minor in studio arts) from Chicago. Within minutes, he has noticed a detail:

“They took old windows from the original church—this rose window, a couple of other windows—and transplanted them into the new building when the congregation moved and the old church was demolished,” he points out.

Making the rounds between the tables covered in historical maps, flyers, old photographs,architectural plans, and Kodak company documents—assembled by librarians Andrea Reithmayr and Melissa Mead—Smoller encourages her students to engage with the original materials.

“Look at the sources, apply the different types of analyses we have covered, then come up with questions, and make an inventory,” Smoller tells them. “Dive in cold. Resist the temptation to look things up online.”

The analytical techniques she is referring to are the four modes that are part of teaching the materials: textual, spatial, visual, and social. “We learned that students did not know what these academic research approaches entailed,” Christensen says. “Teaching this class really became an exercise in taking a step back.”

Smoller tells the students that research is somewhat like making cheese. “Jot down everything, the curds will separate, but somehow in the end it all comes together in a big lump of cheese. Don’t narrow it down too early,” she cautions.

Yaal Dryer ’20 pours over the original building plans for the First Universalist Church. “They took old windows from the original church—this rose window, a couple of other windows—and transplanted them into the new building when the congregation moved and the old church was demolished.”

The metaphor might as well apply to this interdisciplinary class. A lot of curds and whey go into the end product. The trio readily admits that the first year was a steep learning curve. But now they dovetail neatly from lesson to lesson, like a carefully choreographed ballet—make that synchronized cheesemakers.

Sandra Knispel, January 2018