Field guide to fruit flies

Anyone who has ever left an overripe banana on the kitchen counter knows Drosophila melanogaster.

The common fruit fly is often deemed an annoying household pest, meant to be swatted or squashed. What people often don’t know is that these tiny insects offer a plethora of clues about our very selves.

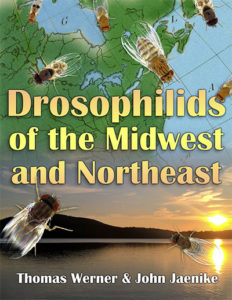

“Fruit flies can reveal a lot about genetics, disease progression, addiction, crop parasites, you name it,” says John Jaenike, a professor of biology at the University of Rochester. Jaenike, along with Thomas Werner, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Michigan Technological University, recently coauthored an open-access field guide, Drosophilids of the Midwest and Northeast. The book documents the physical and behavioral characteristics of fruit fly species in the titular regions and is the first comprehensive guide to fruit flies published in nearly a century.

Although less than a millionth of the size of most humans, fruit flies share about 70 percent of the same genes that cause human diseases. And because fruit flies have such short reproductive cycles—less than two weeks—scientists are able to create generations of the flies in a relatively short amount of time. These are among the key characteristics that make these insects an ideal model for learning more about our own genetics. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 photo / Jim McLean)

Although less than a millionth of the size of most humans, fruit flies share about 70 percent of the same genes that cause human diseases. And because fruit flies have such short reproductive cycles—less than two weeks—scientists are able to create generations of the flies in a relatively short amount of time. These are among the key characteristics that make these insects an ideal model for learning more about our own genetics, inheritable traits, and the progression of such diseases as cancer, Parkinson’s, and diabetes.

“Humans and fruit flies have a common ancestor that lived about 550 million years ago,” Werner says. “Fruit flies are these incredible organisms that are, on the molecular level, quite closely related to humans, which is why they can tell us a lot about humans.”

Jaenike has spent a large portion of his career collecting various fruit fly species and studying and cataloging their unique properties. Both he and Werner hope their new book will allow others to do the same: “Our goal is to show there are a lot of cool species right in your backyard,” Jaenike says. “We want to show people how to identify them, and also teach them about the biology of each species.”

As Jaenike and Werner show, various fruit fly species can be individually distinguished based on size, color, and wing pattern. The behavior of fruit flies offers additional clues. “Some are very sluggish, and others fly around like crazy,” says Jaenike, who has found many species included in the book right here in Rochester.

In a swampy area of Mendon Ponds, for example, he found a Drosophila nigromelanica; previously, this species had only been found in two other places in New York.

In Highland Park, he discovered a Phortica variegata, a “whole genus that had never been seen in North America before.”

He has even caught a rare species of fruit fly on the beer hops discarded in a compost pile behind a local brewery.

“After they’re done making beer, they toss all that stuff in a compost heap,” Jaenike says. “I found a rare species there that is more common down south. Recently, people have been studying how fruit flies can become addicted to alcohol, and, if the underlying biological basis is similar, that could lead to health benefits for humans.”

For the past eight years, Jaenike has focused his own studies on Drosophila neotestacea. This species suffered high levels of female sterility in the 1980s because the flies became infected with a type of nematode (roundworm) parasite. By the early 2000s, many of the parasitized females were no longer sterile. Jaenike and his team studied the flies and found that in addition to having the parasite, they also had a bacterium, which was an inheritable factor passed on from mother to offspring. The bacteria allowed the flies to live with the parasite without negative effects.

Because the nematode parasite is closely related to parasites found on certain crops, Jaenike hopes future research will focus on the bacteria to see what properties are responsible for the antinematode effects. This information would be useful in controlling plant parasites.

Jaenike’s knowledge and enthusiasm is what initially drew Werner to collaborate with him on the field guide.

“When I saw John out in the field identifying fruit flies with his naked eye, I thought, ‘This guy is a genius. We need to preserve this knowledge,’” says Werner, whose current research focuses on the complex color patterns of Drosophila guttifera and various Drosophila species that are resistant to otherwise toxic mushrooms.

The pair collected and photographed average male and female flies for each of the species included in the book. They also included photos of the wings, key identifying traits, suggestions on how to bait and collect the flies, recipes used to feed them, and the intriguing biological characteristics unique to each species.

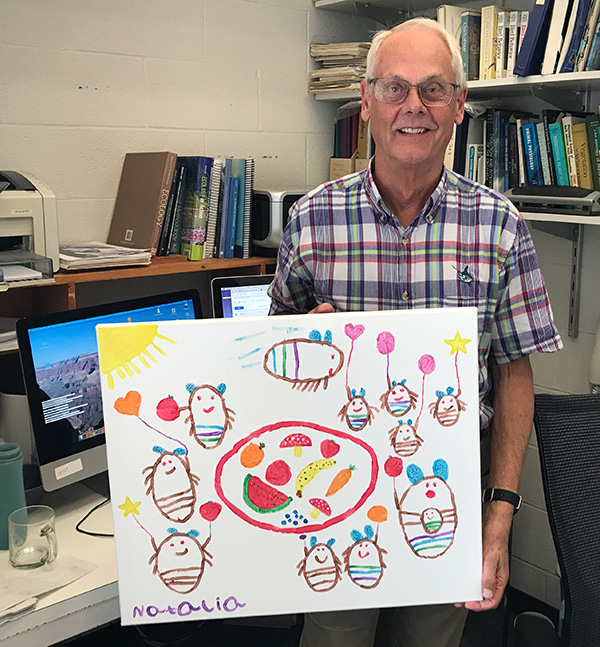

Jaenike and Werner’s immediate goal is to fill in a few gaps; because they were unable to collect and take pictures of all the known regional species, Werner’s then five-year-old daughter and fellow fruit fly enthusiast, Natalia, supplemented the photographs with her own depictions of fruit flies, drawn in marker. One of Natalia’s signed originals is displayed on a large canvas in Jaenike’s office.

For their book, Jaenike and Werner were unable to collect and take pictures of all the known regional species, so they supplemented the photographs with drawings of fruit flies created by Werner’s then five-year-old daughter, Natalia. Here, Jaenike poses with one of Natalia’s signed originals. (University of Rochester photo / Lindsey Valich)

The researchers ultimately hope to replace these drawings with actual species photos, which was a key impetus for publishing through an open-access platform. The pair worked with River Campus Libraries to turn PDF pages into a book available online for anyone to download.

“We wanted to make the book as freely and widely available as possible, in the hope that as many people as possible would use it,” Jaenike says. “The online, free format also means it will be relatively simple to update as we add more species, and will make it easier to include Drosophila from new geographic regions in the future, as well as new species that might invade our area.”

And, while Jaenike is fascinated with studying the flies in his lab and in the wild, he readily acknowledges that he does not want the flies in his home. He offers the following advice for those who want to avoid the insects in their living spaces: “Put apple cider vinegar or beer with a little bit of soap in it. The flies are attracted to that, but they will also drown in it.” Or, a simpler solution? “Don’t leave rotting fruit around.”

Drosophilids of the Midwest and Northeast

Open-access publishing: Questions for Rochelle Mazar

Open-access publishing: Questions for Rochelle Mazar

Drosophilids of the Midwest and Northeast, the new guide to fruit flies coauthored by Professor of Biology John Jaenike, was published through River Campus Libraries in an open-access format. What does that mean? Rochelle Mazar, assistant dean of academic engagement, River Campus Libraries, explains.What is open access?

Open access is immediate, digital access to material—whether a monograph, a journal article, etc.—free of charge and free of most copyright constraints on usage.Can anyone on campus publish open access?

Absolutely. Anyone on campus can contact their outreach librarian (library.rochester.edu/subject-librarians) and say they’re interested in publishing in an open-access venue. Your librarian can help you find the most appropriate place for your scholarship.

What sorts of projects are suitable for open access?

Many projects are a good fit for open access. Any non-profit-generating research that you want the entire world to have access to is a good fit. Because open-access projects live online, research that benefits from being presented in a digital format is a good contender. If you want your research to have widespread and immediate impact, open access might be right for you.

Where can one find open-access publications?

Check out the Directory of Open Access Journals (doaj.org) and the Directory for Open Access Books (doabooks.org). For open-access textbooks, you can visit Open SUNY Textbooks (textbooks.opensuny.org), Open Stax (openstax.org), and Open Textbook Library (open.umn.edu/opentextbooks).

Lindsey Valich, October 2017