Unlocking big data

Unlocking big data

Wegmans Hall opens doors to data science

Named in recognition of the support of the Wegman Family Charitable Foundation, the 58,000-square-foot Wegmans Hall is designed as an interdisciplinary campus hub for work involving data science. Dedicated during Meliora Weekend last fall, the building will open for researchers this year.

The building is home to the Goergen Institute for Data Science, a University-wide center that helps to advance the University’s research strengths in machine learning, artificial intelligence, biostatistics, and biomedical research.

Goergen Institute for Data Science provides new opportunities for collaboration

In 2016, Timothy Dye, a professor of public health sciences, traveled with a team to Puerto Rico to help local medical personnel deal with a Zika epidemic. In the process, they interviewed residents on their attitudes and living conditions, ending up with a voluminous amount of data.

When they returned home, Dye approached Jiebo Luo, an associate professor of computer science who specializes in machine learning, data mining, and biomedical informatics. “Our operation is involved in converting research findings into applications, and that means making sense of massive amounts of data” says Dye. “We knew Jiebo Luo was the right person for the job.”

Dye and Luo are just two of the more than 40 faculty members from across the University whose research either relies on or furthers the new and fast developing field of data science. To harness their strengths, and facilitate collaborations such as the one between Dye and Luo, the University launched the Goergen Institute for Data Science in 2016.

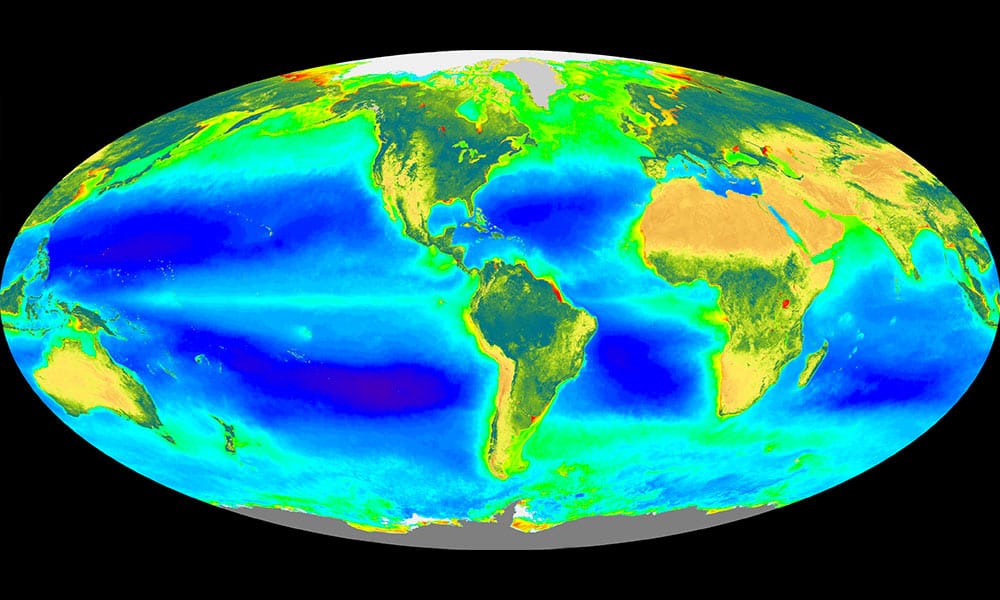

Using data science to understand global climate systems

Climate scientists at the University of Rochester are using data science to understand what drives the global climate system—from deep in the ocean to high in the sky.

Tom Weber, who studies marine ecosystems, and Lee Murray, who studies atmospheric chemistry, both joined the Department of Earth and Environmental Science as assistant professors this academic year. In addition to their individual research, Murray and Weber will be collaborating on a joint project funded by NASA, in which they will use models and satellite data to explore the global methane cycle and exchange of methane between the atmosphere and ocean and freshwater lakes.

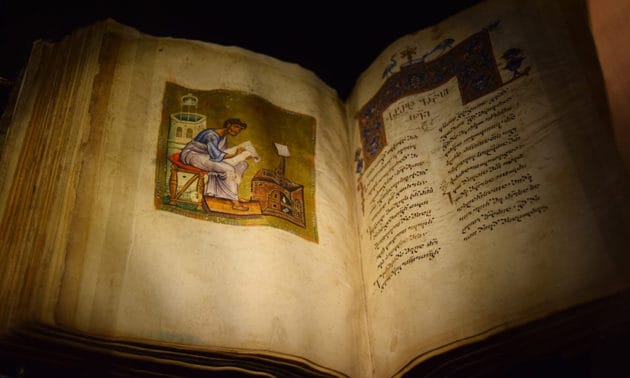

The future of the past

Pack lightly, seasoned travelers advise. Take only what you need.

And Gregory Heyworth, an associate professor of English, does. A scant collection of clothes makes it into his bags when he flies to Italy, or the former Soviet republic of Georgia, or Wales. He pares his wardrobe to make room for the camera, light-emitting diodes, computers, and other pieces of equipment that fill his luggage instead.

Trained as a scholar of medieval literature, Heyworth has become—in a term he coined—a “textual scientist.” He recovers the words and images of cultural heritage objects that have been lost, through damage and erasure, to time.

A new way to teach history in the 21st century

The “Oven Site” that Mike Jarvis and his students have been excavating the last five summers is 1,024 miles away in Bermuda, protectively buried under five feet of earth.

But at any time, on any day, Jarvis, an associate professor of history at the University of Rochester, can walk across campus to the Carlson Science and Engineering Library and instantly project a life-like 3-D rendering of the site—just as it looks when fully excavated—on a 20-foot-by-8-foot screen.

It’s a graphic tour de force, and a great example of the data visualization capabilities of the University’s VISTA (Visualization-Innovation-Science-Technology-Application) Collaboratory.

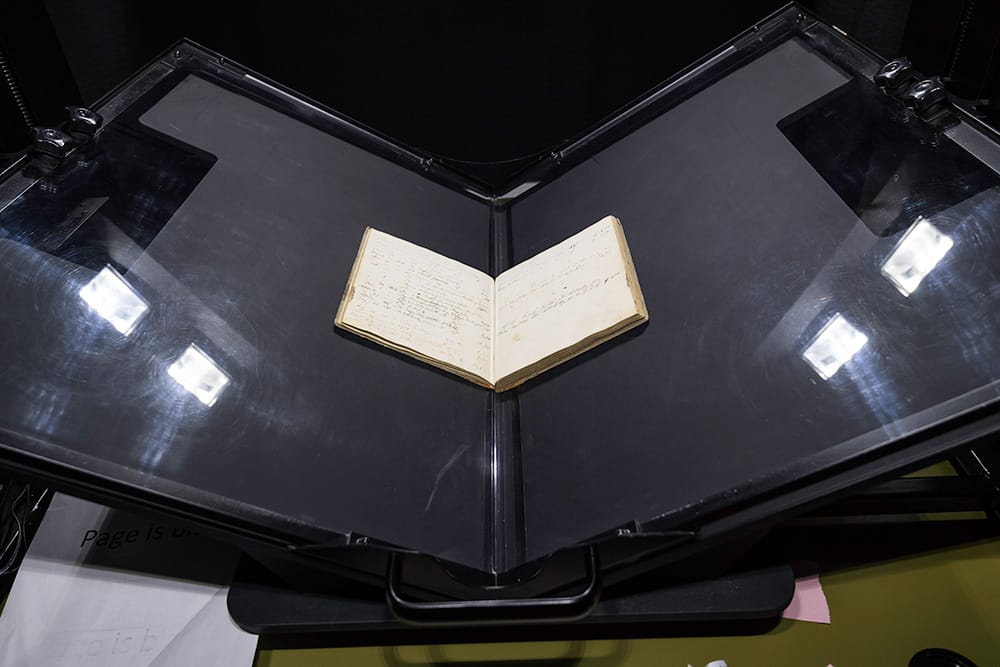

Big library, big data

“Libraries have been managing data for centuries,” says Marcy Strong, head of metadata service at River Campus Libraries. And in the new field of data science, practitioners will rely on work University librarians have long done.

Librarians’ expertise in data standards, tools, and models, makes them integral to enterprises in data science. The newly created Digital Scholarship Lab, housed in the Humanities Center in Rush Rhees Library, is designed to give researchers the tools and software they need to develop new methods of analyzing a wide range of data.

Unlocking the secrets of blue notes

What makes a great singer in the tradition of jazz, rock, or blues? It is not only vocal quality and emotional expression, but the actual notes sung—and not just the usual notes on the piano keyboard. In the words of the late Marvin Gaye: “There’s got to be other notes some place, in some dimension, between the cracks on the piano keys.”

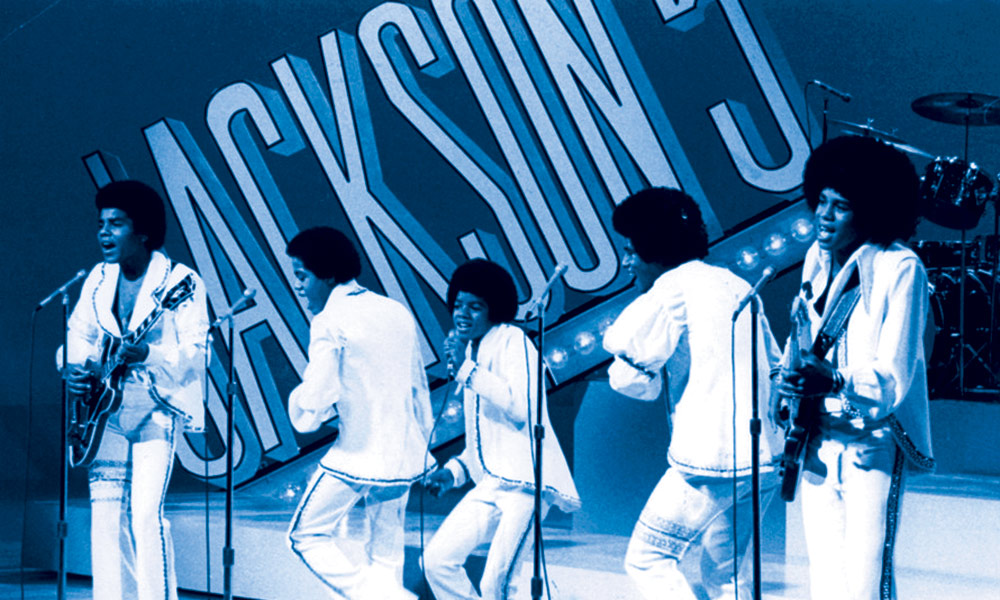

In the musical realm, these notes “between the cracks” of conventional pitches are called blue notes. Researchers at the University of Rochester are using advanced tools of music technology to unlock the secrets of blue notes. Professor of music theory David Temperley and his team studied blue notes in the context of rock and pop songs such as the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction,” the Eagles’ “Take it Easy,” the Beatles’ “Can’t Buy Me Love,” and Jackson 5’s “ABC.”

Career Center using data to connect students, employers

When Joe Testani took over as executive director of the Career Center two years ago, his goal was to hire someone with an expertise in analyzing data that would benefit students and prospective employers. Last July, he brought in Vanessa Newton as director of assessment data and operations. “Now, we have someone creating dashboards and syncing data,” Testani says. “We can determine who’s seeing us,” he adds, referring to the Career Center website, as well as “what kinds of students are seeing us and how often, and how many alumni are we engaging. It’s a big part of what we do.”

A student or alumnus “can go online and see that, just because you have an English degree or a psychology degree, it doesn’t mean you have to work for a certain company,” Newton says.

Skin sensors provide wealth of patient data

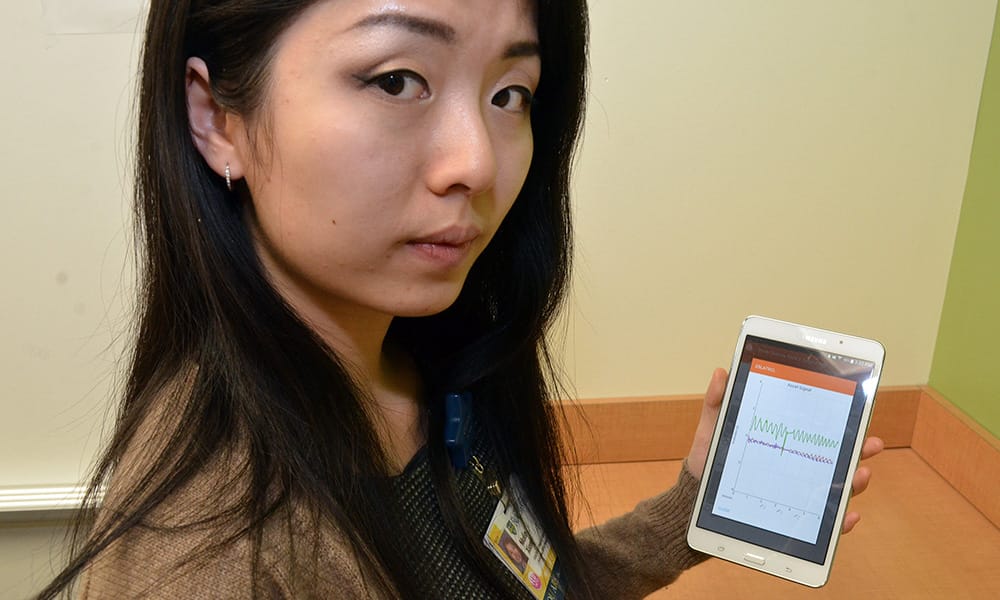

“Instead of treating all patients as averages, which none of us are, we will be able to customize treatment based on individual data,” says Gaurav Sharma, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. He is collaborating with University neurologist Ray Dorsey on a study which they hope will help improve treatment of patients with Parkinson’s or Huntington’s disease.

So how does one analyze some 25 million measurements generated by these sensors for each patient over a two-day period? And then present the results in ways that are intelligible to a physician? That’s where data science comes in.

Machine learning advances human-computer interaction

Machine learning, a subfield of artificial intelligence, started to take off in the 1950s, after the British mathematician Alan Turing published a revolutionary paper about the possibility of devising machines that think and learn. His famous Turing Test assesses a machine’s intelligence by asking whether a person is able to distinguish a machine from a human being.

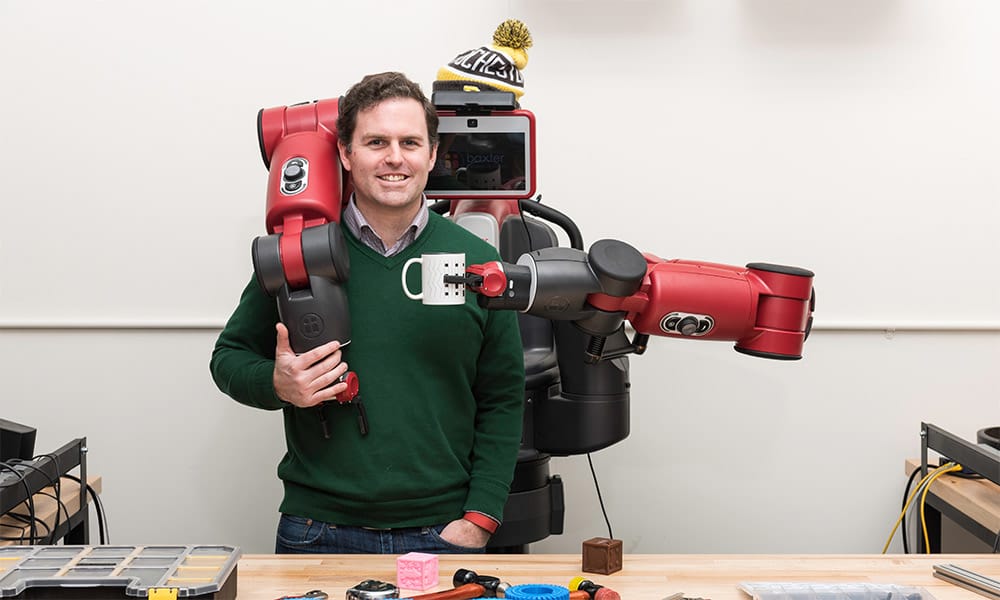

Today, Thomas Howard ’04, director of the University’s robotics lab, joins other Rochester researchers in developing computer models that detect patterns, draw connections, and make predictions from data to construct informed decisions about what to do next.

The mysteries of music—and the key of data

There’s much that’s mysterious about music.

“We don’t really have a good understanding of why people like music at all,” says David Temperley, professor of music theory at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. “It doesn’t serve any obvious evolutionary purpose, and we don’t understand why people like one song more than another or why some people like one song and other people don’t. I don’t think we’re anywhere near uncovering all of the mysteries of music but there are a lot of questions that people are starting to answer with data science.”

As Temperley says, “There is a lot you can quantify about music.”

QuadCast: ‘When you have big data, you can get very lost’

As is true in many fields, education researchers now have unprecedented access to large public data sets, and new methods and tools for analyzing that data. What does this mean for the kinds of questions you can ask when you are interested in, for example, recruiting administrators in small rural districts in Texas, or understanding the impact of spending money on metal detectors versus school counseling services? And how do you avoid getting overwhelmed by the sheer volume of available data?

In this episode of the QuadCast podcast, Nick Bruno ’17 talks with two researchers at the Warner School of Education—Kara Finnigan and Karen DeAngelis—who are using data science to understand the challenges facing K-12 education, both here in Rochester and around the country.

GPS sensors give women’s soccer team analytic edge

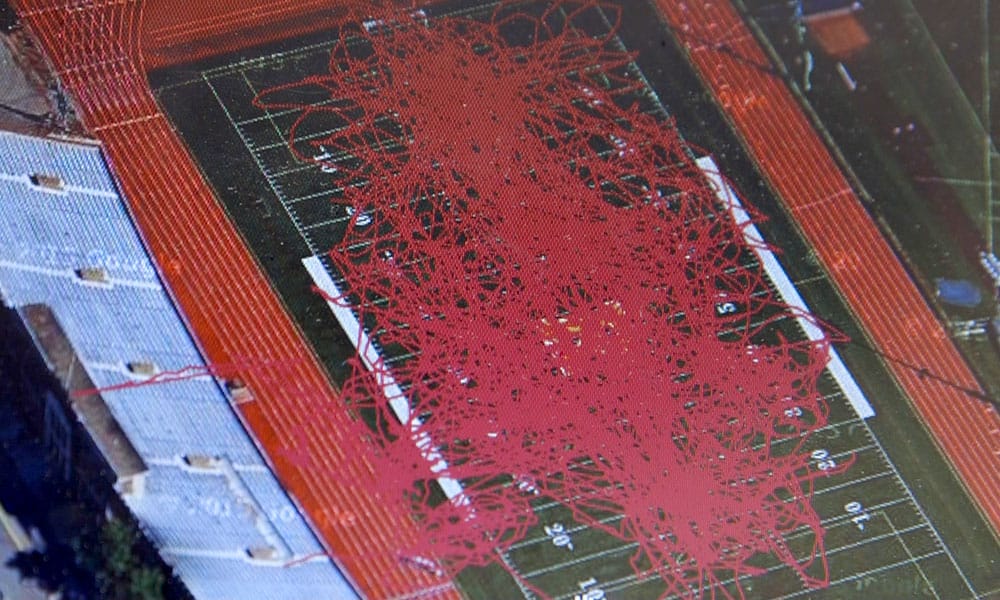

Kim Stagg ’17 covers a lot of ground during each soccer team practice and game. In fact, she left cleat marks over 90 percent of Fauver Stadium.

“She was everywhere,” Yellowjackets coach Thomas (Sike) Dardaganis says.

Dardaganis knows this because he has the heat map and data to prove it. In an innovative data analytics program, Stagg and her teammates wear GPS devices that track movement, heart rate, and exertion levels, helping her coaches know how much recovery time she might need to avoid injury.

Student athletes find big wins in big data

From basketball to golf, field hockey to football, the Yellowjackets rely on statistics to evaluate players, opponents, and strategy. Data analytics is the new normal for college teams, with programs using different web-based tools to evaluate student-athletes, plan for opponents, and even prevent injuries. “What we have now is so much better than just a few years ago,” says men’s basketball coach Luke Flockerzi. “I can’t imagine what’s in store in the years ahead.”

Data science for a better planet

Ulrik Soderstrom ’16, ’17 (MS), has found myriad ways to apply his knowledge of data science and machine learning: everything from bringing solar energy to low-income communities, predicting weather patterns for farmers, modeling ocean wave patterns, and solving Sudoku puzzles.

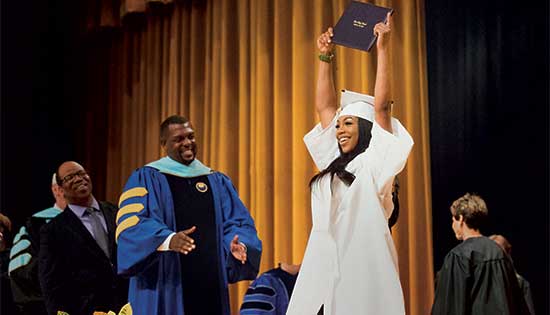

Soderstrom is one of the first students to graduate with a BA in data science (and a joint BA in Earth and Environmental Science), and also go on to the data science master’s degree program, which he will complete in May. Along with finishing his coursework, he is currently working as a data scientist with Arable Labs, where he utilizes machine learning algorithms to create weather forecasts from aggregated weather data, and a data science consultant for ROCSPOT, where he connects utilities, homes, and corporations to solar installers to increase usage of solar power.

Millions of tweets are a gold mine for data mining

Computer scientist Henry Kautz likens Twitter to a kind of distributed sensor network. Hundreds of millions of tweets are posted to the platform each day, with each user observing and reporting on some aspect of the world.

“Each report is very noisy,” says the Robin and Tim Wentworth Director of the Goergen Institute for Data Science. “But the aggregate results can be reliable.”

Those results can provide Rochester’s data scientists with information to meet all kinds of challenges–from public concerns regarding health, safety, and the environment, to private ones regarding client and customer satisfaction and changing consumer tastes.

Twitter researchers offer clues for why Trump won

Jiebo Luo and Yu Wang did not set out to predict who would win the 2016 U.S. presidential election. However, their exhaustive, 14-month study of each candidate’s Twitter followers–enabled by machine learning and other data science tools–offers tantalizing clues as to why the race turned out the way it did.

Luo and Wang, a dual PhD candidate in political and computer science, summarized their findings in eight papers during the course of the campaign. They found, for instance, that the more Donald Trump tweeted, the faster his following grew–even after he performed poorly in debates against other Republican candidates, and even after he sparked controversies. Also, the percentage of female Twitter followers in the Clinton camp was no larger than that in the Trump camp. Moreover, though “un-followers” were more likely to be female for both candidates, the phenomenon was “particularly pronounced” for Clinton.