The mysterious aftermath of an infamous pirate raid

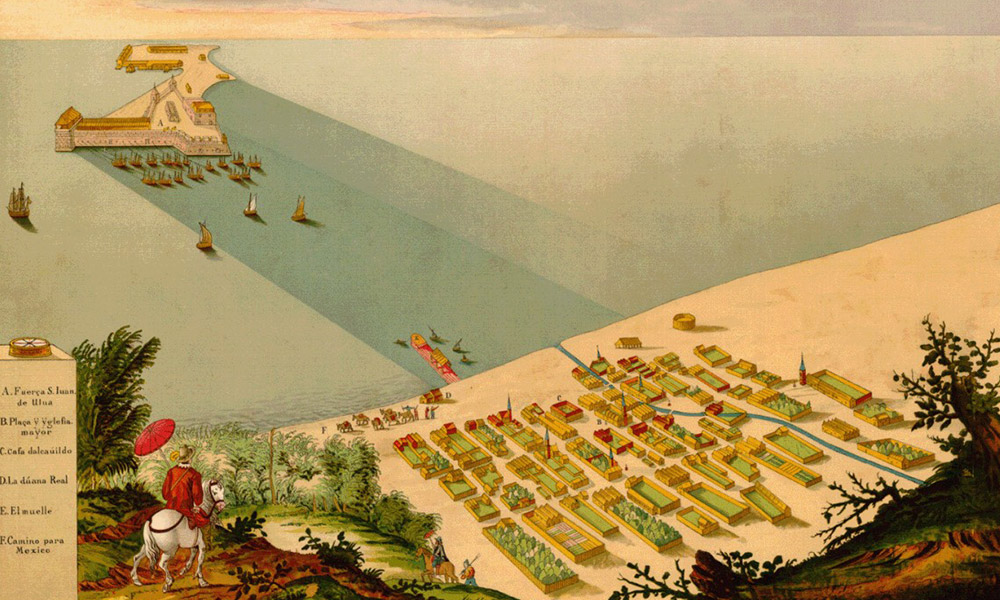

Just before dawn on May 18, 1683, pirates stormed the port city of Veracruz in the Viceroyalty of New Spain on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, easily overwhelming its Spanish military defense. For two weeks, the buccaneers, led by the Dutch Laurens de Graaf and several hundred French and English associates, wreaked havoc. They raped and looted, pillaged and exhorted steep ransoms for the release of valuable hostages.

“But the ultimate crime is what they did in the end,” says Pablo Sierra Silva, an assistant professor of history at the University of Rochester. “They kidnapped the entire population of African descent, because slavery is expanding in the English and French colonies at this time and there’s now a market for such captives.”

Just before their departure on May 31, the pirates captured between 1,000 to 1,500 Veracruzanos and loaded them onto their fleet of 13 ships. Then they set sail for the pirate sanctuary of St. Domingue, modern-day Haiti. There, they sold their human cargo—some slaves, some formerly free residents of Veracruz singled out by the pirates for their darker skin—to slave masters in St. Domingue, and nascent Charleston, South Carolina. While history remembers the violent raid on Veracruz, little is known about its victims.

The port of Veracruz in 1615. (University of Texas Libraries photo)

“That singular extraction and then dispersal of these people has never been studied,” says Sierra Silva.

The historian joined the Rochester faculty in 2013, straight out of the doctoral program at the University of California, Los Angeles. His first book, Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Ángeles, 1531–1706, is due out from Cambridge University Press in March 2018.

But he’s already embarked on research for his second book, which will trace the paths of those forgotten Afro-Veracruzanos. Sierra Silva got a big boost this month when the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) awarded him a $50,400 fellowship to support the project, titled Mexican Atlantic: Contraband, Captivity and the 1683 Raid on Veracruz.

Sierra Silva will reassess Veracruz’s history by focusing on a moment in which free and enslaved men and women of African descent were made captives (in some cases, re-captives). The grant will enable him to spend the next 12 months travelling to colonial archives and repositories in the US, Spain, and Mexico. He’ll work at the Archive of the Indies in Seville, the John Carter Brown Library in Providence, Rhode Island, the University of South Carolina, the South Carolina Historical Society, and the College of Charleston.

Sierra Silva is also winning praise from his Rochester colleagues. “He’s is a talented researcher and a valuable contributor to the overall strength of the School of Arts and Sciences,” says Gloria Culver, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. Matthew Lenoe, an associate professor of history and chair of the department, says he is “tremendously excited” about Sierra Silva’s NEH award.

“Pablo richly deserves it,” Lenoe says. “His work on the history of African slavery in Mexico and its ramifications throughout the Atlantic World breaks paths into an important and understudied area. Innovative and timely, it is also based on research in rarely used 17th-century archives.”

Assistant professor of history Pablo Sierra Silva teaches his “Samba, Vargas, and Brazilian Identity” class in Spring 2014. (University photo / Brandon Vick)

The project makes for a compelling historical mystery. With painstaking planning, the pirates originally took their high-value hostages, including Don Luis de Córdoba, the governor of Veracruz, and members of the Catholic clergy to the nearby tiny Isla de Sacrificios (Island of Sacrifices). Once the ransoms were paid, the pirates returned the hostages to Veracruz. But up to a fourth of the port city’s then small population of about 6,000 people remained captive. The captives—people of African descent, many of whom had intermarried and intermixed with the Spanish and indigenous population, some already Veracruzanos in the second or third generation, were deemed mulatos, pardos, negros and morenos. Regardless, the pirates loaded them up and sold them into slavery.

“They were gone overnight,” says Sierra Silva. “It’s a shocking human-orchestrated catastrophe” that decimated the city by about 25 percent.

So far he has discovered archival references to five local women who were able to escape captivity in the Caribbean. Over the course of several years, they managed somehow to make their way back to Veracruz, arriving—in an ironic twist—as passengers on a Dutch slave ship.

It’s these scraps of memory that the historian is now seeking, as he lays out his case that the colonial histories of Mexico and the United States are intimately connected through the infamous 1683 pirate raid.

“Traditionally in Mexican history we tend to be fairly insular,” Sierra Silva says. “It’s almost as if it weren’t entangled somewhere with the history of South Carolina, the history of St. Domingue. What I started to realize when researching this pirate attack is that, in fact, these colonial experiences are completely intertwined.”

In the months following the raid, no fewer than 200 Afro-Veracruzanos were sold in Charleston, which was still half a century away from the mass arrivals of the plantation-driven slave trade. At the time of the pirate attack, the English settlement in South Carolina was still in its infancy. The victims of the raid would have accounted for well over a fifth of young Charleston’s population of African descent.

By tracing the paths of those who disappeared, Sierra Silva’s project seeks to recover the experiences of enslaved people in numerous settlements throughout the Spanish, English, French, and Dutch Atlantic during the 17th century.

“Of course, they leave relatives further inland. They leave cousins, business associates, godchildren. Part of this project is to look at how they remember the lost,” Sierra Silva explains.

“We have fragments, little strands of evidence that suggest that, of course, people don’t forget.”

Sandra Knispel, December 2017