East High vision care program teaches and heals

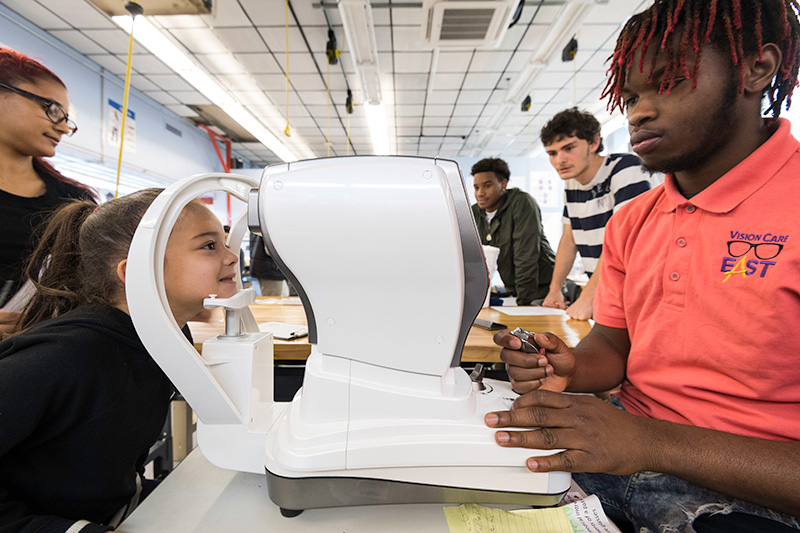

Janarelis Perez, a first grader at School 34 in Rochester, is worried. “Does it hurt? I’m scared,” she blurts out as optometrist Pat Weisenreder sits her down for an eye exam.

Janarelis, who lost her glasses some time ago, is so nervous she can’t stop chattering. Weisenreder tries to reassure her. As it turns out, the six-year-old is less worried about pain than about getting the answers wrong as she struggles through reading (or rather, guessing at) the eye chart on the wall. Without glasses, she’s lost.

What makes the encounter unusual is that it does not take place at a doctor’s office, but instead at Rochester’s East High School. Weisenreder is part of a small group of local optometrists and ophthalmologists who volunteer time at the school providing free eye exams and prescriptions. Here, students enrolled in the school’s vision care program build eyeglasses for the patients—kids in Rochester city schools—without charge.

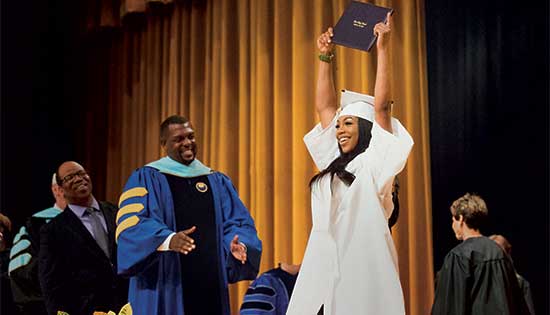

East High 9th grader Kumari Lamgade receives an eye exam through the school’s vision program. The program trains high school students in the optometry field while providing vision care services for fellow students. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

A moment later, with Janarelis’s prescription in hand, the high schoolers go to work, running through the four main stages of producing prescription eyewear: spotting and dotting, blocking and decentering, edging, and inspecting the finished product. The primary schooler, meanwhile, is hopping from one foot to the other, excited that she’ll once again be able to see at school.

Janarelis is not the exception, says Logan Newman, the teacher in charge of East’s vision program. “It’s amazing, but a lot of the kids don’t realize they can’t see.” Their grades suffer unnecessarily, and so, often, does their morale and attitude. “I know I have kids where we really made a difference with our program,” says Newman, who has been right there when kids get their first pair of glasses and suddenly realize what they’ve been missing.

School 34 first grader Janarelis Perez, 6, undergoes measurements at the auto refractor machine operated by East 12th grader Kendrick Martin. The school’s vision care program trains high school students to graduate into jobs in the optical field, while helping a critically underserved community. This combination makes it the only such program of its kind in the country. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

A former US Navy medic with training as an optician, Newman later graduated from college with a degree in biology and became a certified science teacher. In 2012, New York state awarded him a STEM grant to start developing the curriculum for East High’s vision program. In 2014, he added his own New York state-certified optician’s license so that the school could legally start dispensing glasses.

The school’s three-year vision care program trains high school students to graduate into jobs in the optical field, while helping a critically underserved community. This combination makes it the only such program in the country, says Newman.

It’s an obvious win-win. In addition to acquiring job skills that allow them to apply directly for entry-level jobs as optical technicians, the students also collect college credits toward a degree in optics at Erie Community College in Williamsville, New York. Meanwhile, the program provides many Rochester children their only chance of getting much-needed eyeglasses. Newman estimates about 2,000 Rochester students have received glasses at East since 2014.

Corporate sponsorship has played an important role: Rochester Optical, Jonas Paul Eyewear, Marchon, Eyewear by R.O.I., Safilo, and several other frame manufactures have donated hundreds of frames to the program. With the STEM grant in hand, East was able to buy optical machinery to support the vision care program, as well as a second pathway-to-career program, in precision optics, located directly across the hall.

On a recent Wednesday morning, Newman divvies his second-year students into small groups and tasks each team with building four pairs of glasses from real prescriptions. He works closely with Yamaraitza Vega, a 2016 East High graduate, who is now employed by the program as full-time lab manager and oversees a scattering of third-year students serving as team leaders for today’s hands-on production.

School 34 first grader Janarelis Perez, center, tries on glasses frames as fourth grader Santana Montalvo models a new pair. “It’s amazing, but a lot of the kids don’t realize they can’t see,” says Logan Newman, the teacher in charge of the vision program, which has provided many students with their first pair of glasses. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

The students won’t be just honing their technical competence during the exercise. They’ll be developing softer skills as well.

“When you make glasses as part of a team, each individual has a role that matters,” Newman tells the students. “Trust is important. Each of you is interdependent on the other.”

Most nod, but Willito Soto, a 10th grader, hesitates. “What if something goes wrong?” he worries aloud to his teacher. “Then it’s on me.” Soto tells Newman a team member hasn’t been listening to instructions. “Help her learn that she, too, has a responsibility,” Newman insists.

As the students work, Newman talks about his plans for expanding the program. He wants to organize a job conference with managers in the optics field to ensure more of his students can find well-paying jobs. And he hopes that East’s educational partnership with the University of Rochester will help him enlist the Medical Center’s Flaum Eye Institute. His dream? To make a rotation at East High’s vision care a fixed stop on every Flaum resident’s training schedule.

“We simply need more doctors to volunteer their time,” Newman says. “If a doctor can come here for several hours once or twice a year that would really make a difference in the life of a child.”

At the end of the class, Newman sidles up once more to Soto. “Did it work out?” he asks. “Yeah,” comes Soto’s answer.

“I’m proud of you,” Logan tells his student who lifts his hand to accept his teacher’s high five.

Sandra Knispel, November 2017