AIDS remembrance quilt resurfaces after 23 years

In the spring of 1994, Linda Dudman, associate director of health promotion at the University Health Service, carefully folded a 12-foot square panel from the AIDS Remembrance Quilt and tucked it into a copy paper box, which she placed into a blue storage tote.

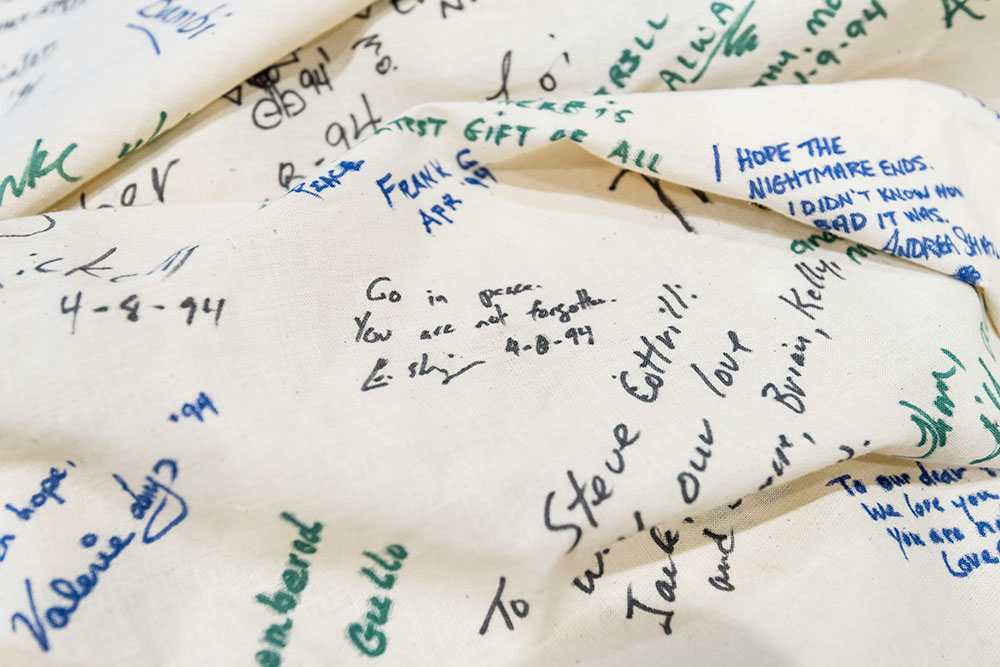

The panel bears the signatures, comments, and tributes of members of the University and the greater Rochester community, many of whom had family members and friends who died of AIDS. The messages, written in blue, green, and black marker, range from the political – calling on bureaucracies to “wake up” – to the deeply personal: “Jim, You will never be forgotten. I was more because of you.”

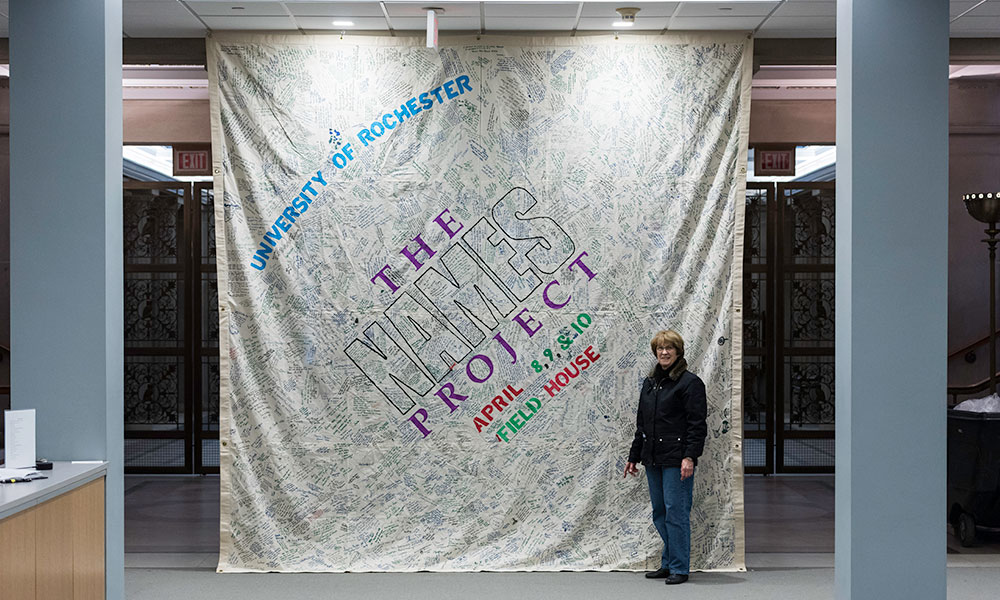

A panel signed by University students and community members and that accompanied the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt when it was displayed in the Field House in Goergen Athletic Center in 1994 is seen in Rush Rhees Library where it will be on display until February 26. The 12’x12′ banner was recently donated to the library’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation by University Health Service’s associate director of health promotion Linda Dudman (above) after 23 years in storage. (University photo / J. Adam Fenster)

Since then, the University of Rochester’s panel had lain in the basement of Dudman’s home in Rochester until she was packing up to move house.

“I knew I had it,” Dudman says. “I knew it was a very important item to keep, but I never quite knew what to do with it.”

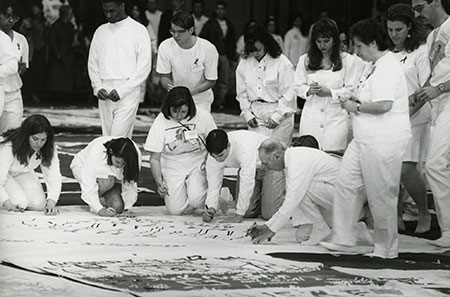

The NAMES Project AIDS Quilt on display in Goergen Athletic Center in 1994. (University photo / Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

The Rochester panel had been signed during the display of the national NAMES Project AIDS Quilt, which contains more than 48,000 individual 3-by-6-foot memorial panels, and which had come to the University in early April 1994. Back then, it had taken a year of planning, a total of 12 committees, and more than 600 volunteers to stage the national AIDS quilt, which was so large that it covered most of the 13,500 square-foot artificial turf inside the Field House at the Goergen Athletic Center.

Now, with its dust shaken off, the Rochester AIDS Remembrance Quilt will once again go on display. A reception is set for February 22 from 4 to 5:30 p.m. in the Hawkins Carlson Room in Rush Rhees Library. The 12-foot square will be displayed at the library’s Lam Square from February 18 through February 26.

At the reception, veteran AIDS experts William Valenti, a clinical associate professor of medicine at the University and senior vice president of strategic advancement at Trillium Health, and Michael Keefer, director of the HIV Vaccine Trials Unit (also known as the Rochester Victory Alliance), will speak about their experience in treating HIV/AIDS patients and their research into finding a vaccine, respectively.

In 1981, when AIDS was first identified among young gay men in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York City, the United States quickly became the epicenter of the world pandemic. The danger of its transmission—imagined and real—facts mixed with folklore, widespread homophobia, and a slow governmental response, created an atmosphere of fear that gave rise to the misconception that only the gay community was at risk.

“Is there ever going to be a cure?” John P. Cullen, director of diversity and inclusion at the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of the Medical Center, remembers asking himself as a newly minted pharmacology graduate in 1995. That year would mark the height of the epidemic in the United States when almost 50,000 Americans died from AIDS.

Fast forward nearly two decades: by 2014, the number of deaths in the United States had dropped to about 12,000. Globally, AIDS-related deaths fell from about 2 million in 2005 to about 1.1 million in 2015. A major factor in the decline was the introduction of antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV/AIDS. Suddenly the diagnosis, while life-altering, no longer meant an automatic death sentence.

Meanwhile, Dudman is happy to have found a permanent home for the quilt: she is donating it to the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation from where it will travel to venues around the University for display. Dudman hopes that returning the artifact above ground will increase awareness among today’s millennials – born well after the height of the AIDS crisis.

“It seems to many of us that AIDS is not a topic that students think about very much, or know much—know that there are medicines that can help,” Dudman concedes. She hopes the quilt display will drive home the message that “AIDS is something that is important to continue to think about.”

Members of the community leave their own messages on a panel that accompanied the national AIDS quilt when it was displayed on campus in 1994. That panel is now on display in Rush Rhees Library, 23 years later. (University photo / Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

Helping Dudman organize the event is Christina Beechert ’17, a mathematics major and pre-med student from Yorktown Heights, New York. “A lot of people our age don’t realize the panic and hysteria of the AIDS crisis when it first happened,” says Beechert. She got involved after hearing Valenti speak last year about his experience in treating AIDS patients at a time when so much was unknown. “So many people our age have no idea how scary it was,” she says.

To Cullen, who is also the assistant director of the Susan B. Anthony Center, the Rochester panel represents a direct window into history. “At present, HIV/AIDS is no longer considered a deadly disease, and people live long lives if they are on retroviral therapy. The struggle that occurred during the eighties and nineties with government and big pharma – a lot of that has been hidden in our history and younger generations aren’t aware of it,” Cullen says. “So we’re hoping this quilt display will make people inquisitive.”

Despite treatment advances, Cullen cautions, this is not the time to let one’s guard down. One in five new diagnoses in the United States are made among 13- to 24-year-olds. Most at risk for infection, Cullen says, is the transgender community and young black men who have sex with men.

While a vaccine against AIDS remains elusive, research is promising. Cullen points to an ongoing study by the Medical Center’s Rochester Victory Alliance, one of the first research sites in the country to conduct HIV vaccine studies, starting in 1988. Michael Keefer is the principal investigator of the ongoing Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) study, which currently tests an experimental antibody against HIV.

Meanwhile, the national NAMES Project AIDS quilt still has one panel missing, a hole left on purpose for a panel that was sewn already back in 1988. In white letters on a stark black background it simply reads “The Last One.” A hope that is echoed by activists, victims’ families, and researchers worldwide.

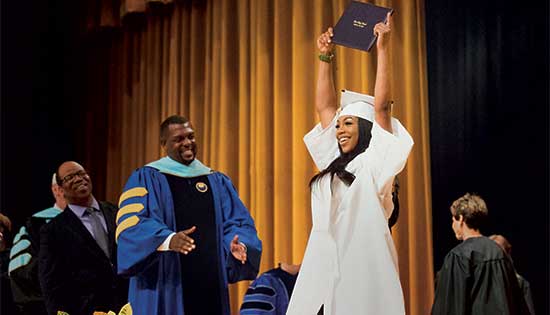

(University photo / J. Adam Fenster)

—Sandra Knispel, February 2017