12 surprising facts about campus spaces

12 surprising facts about campus spaces

1. Washtubs make good chandeliers.

Paul Burgett ’68E, ’72 (Mas), ’76E (PhD), and University leader, talks about the washtubs-turned-chandeliers in Our Work Has But Begun, a history of the University of Rochester from 1850-2005:

“The ceiling light fixtures on either side of the upper balcony of Eastman Theatre (now Kodak Hall) are original though were not part of the initial lighting plans. The intention was to install small crystal chandeliers, miniature versions of the grand central chandelier suspended in the center of the ceiling. The small ones didn’t arrive in time, so an enterprising construction worker acquired two washtubs, painted them gold, decorated and wired them, affixed light bulbs, and hung them from the ceiling. Those original washtubs remain in place today. Should you be in the theater, have a look at the base of these fixtures, and you’ll recognize the familiar concentric washtub circles.”

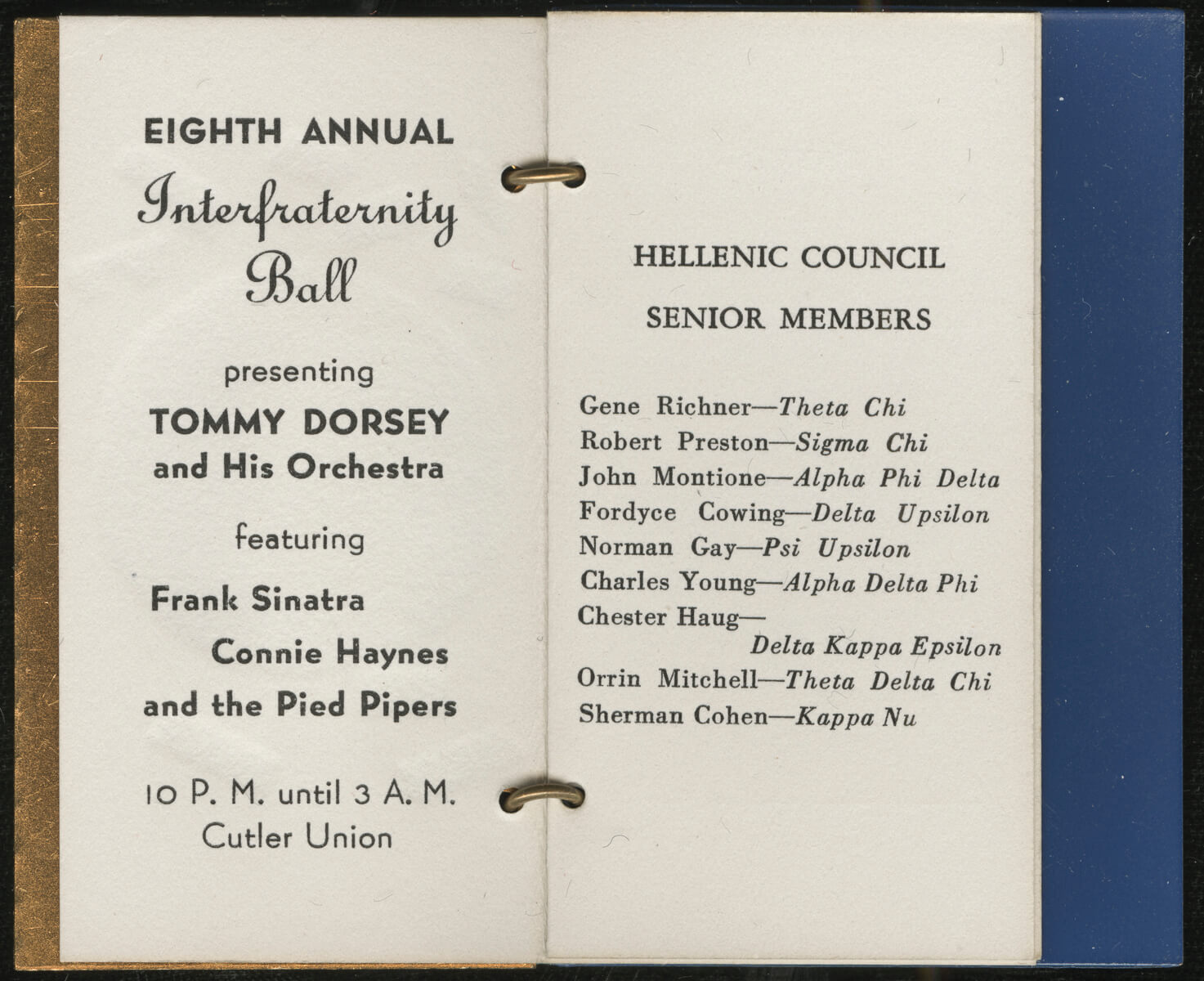

2. Frank Sinatra got his start here. Sort of.

Some big names graced the stages of the University over the years. For instance, at the Interfraternity Ball in May 1941, an unknown singer was introduced with Tommy Dorsey’s band, the Pied Pipers, and played Cutler Union on the Women’s Campus on Prince Street (which later became part of the Memorial Art Gallery). That singer was Frank Sinatra, or as the local paper called him, “Frank Sonatra.” Over the course of several decades, the River Campus hosted other big names, too, such as Buddy Guy, Son House, New Riders of the Purple Sage, The Call, 10,000 Maniacs, Judy Collins, Collective Soul, They Might Be Giants, Fun, and many others.

Listen to a MAG “story walk,” an oral telling of what big band visits to the University—including Frank Sinatra’s—meant to one alumna, as told by her daughter.

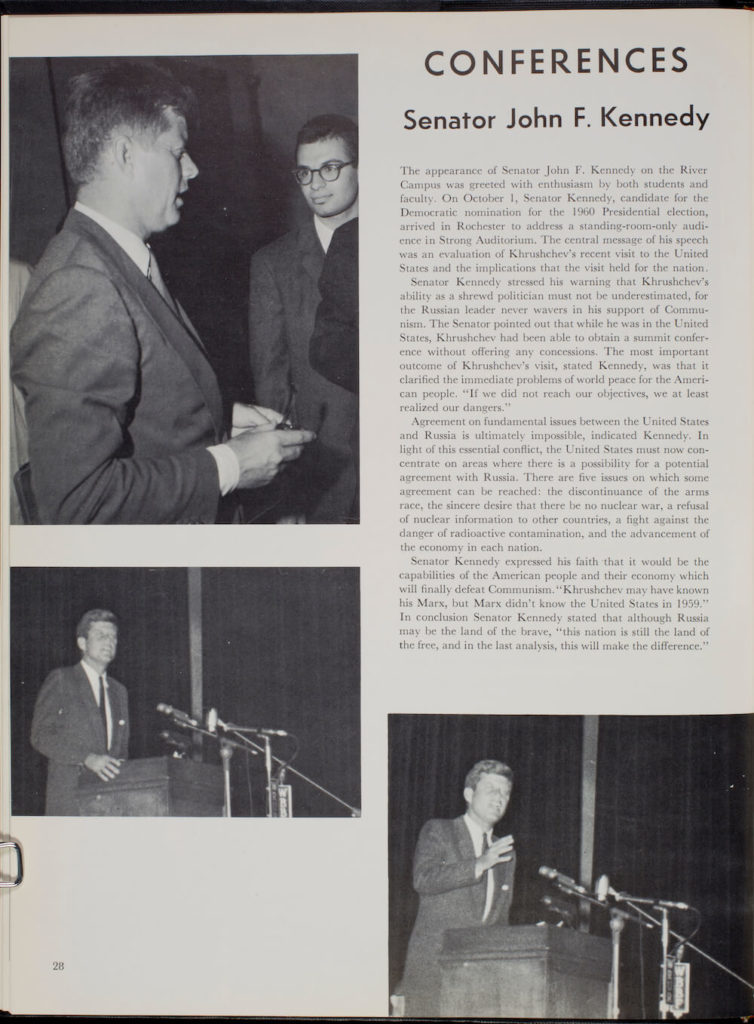

3. World leaders made history here.

Take John F. Kennedy, for example. In 1959, he visited campus as a Democratic senator from Massachusetts seeking the Democratic nomination for president. He greeted an enthusiastic, standing room only crowd on the River Campus, and he spoke about Russia and the Cold War. Eleanor Roosevelt was another visitor. In 1950, she spoke at Eastman Theatre and then participated in a student-run conference on human rights at Todd Union. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill also “visited” campus in 1941, but he did so over the radio waves. He accepted an honorary doctor of laws from London through a trans-Atlantic radio address that encouraged Anglo-American unity in the fight against the Nazis.

4. A Memorial Art Gallery kiln helped fuel the war effort.

By the time the United States formally entered World War II, Brian O’Brien, the director of the Institute of Optics, and his colleagues had “essentially initiated the whole science of night warfare,” writes faculty member Carlos Stroud in A Jewel in the Crown, the history of the institute that he co-wrote and edited.

Then, by the end of World War II, about half of the country’s university-based military optics research projects were conducted at the University of Rochester. Even the ceramic kilns of the Memorial Art Gallery were taken over for molding aspheric lenses for aerial cameras. Four days a week, art students suspended the firing of their work for this important research project.

Read about this and more in “When War Came to Campus,” a fascinating look at how America’s entry into World War II changed and challenged the lives of Rochester students and faculty.

5. The naval science building was literally built like a ship.

Opened in 1946 as a naval science building, Harkness Hall on the River Campus was laid out like a ship. It contained offices and classrooms, a naval library, a practice range, navigation instruments, and equipment used to teach naval tactics. ROTC students regularly held dances in the building.

6. The Meliora Madams stand for knowledge. Literally.

Commissioned in 1874 by Hiram Sibley, the four statues that stand between Meliora Hall and Rush Rhees library each represent a branch of knowledge. Eight statues originally made up the group. Hailing from Carrera, Italy, two were believed to have been damaged during the journey to Rochester—lost in the Hudson River or Erie Canal. The remaining six were installed in the niches of Sibley Hall on the original Prince Street campus. By 1968 when Sibley Hall was razed, one was too badly damaged to be salvaged. Four statues eventually came to the River campus and another—representing Commerce—made her way to Canada, and was returned in 2013 to join three of her sisters—Geography, Astronomy, and Science, which had been restored back in 1980 thanks to the generosity of the Class of 1954. Today, Commerce stands at the end of Dewey Hall, near the Simon School. (Logistically, because of the landscaping, it wasn’t possible to put her with her “sisters.”)

7. Flag rushing meant a pretty certain fate for freshmen.

The tradition of flag rushing began on campus in the late 19th century and lasted until 1964. Victory was declared by the freshman class if they captured the flag, which happened to be affixed atop a well-greased pole. Sophomores fiercely defended the flag (the use of rotten tomatoes was a common munition), and the attacking freshmen would rarely, if ever, win. Their fate? They had to wear their freshmen beanies until the end of the first semester and they were “required” to only use the tunnels (and not be seen above ground walking the Quad). But, the freshmen gained some useful knowledge of the tunnels along the way, something that served them well in the cold winter Rochester months when nary a person wanted to walk across the Quad anyway.

More tunnel trivia

More tunnel trivia

The tunnels were originally built for facility maintenance purposes. When they were opened to students at the start of the 1930 academic year, campus leadership didn’t think students would use the tunnels because the campus was so beautiful. But, by November of that year, the tunnels were full of students who wanted to escape the cold.

The tradition of painting the tunnels began in the late 1960s and today serves as a way for the campus community to express itself and communicate events and activities.

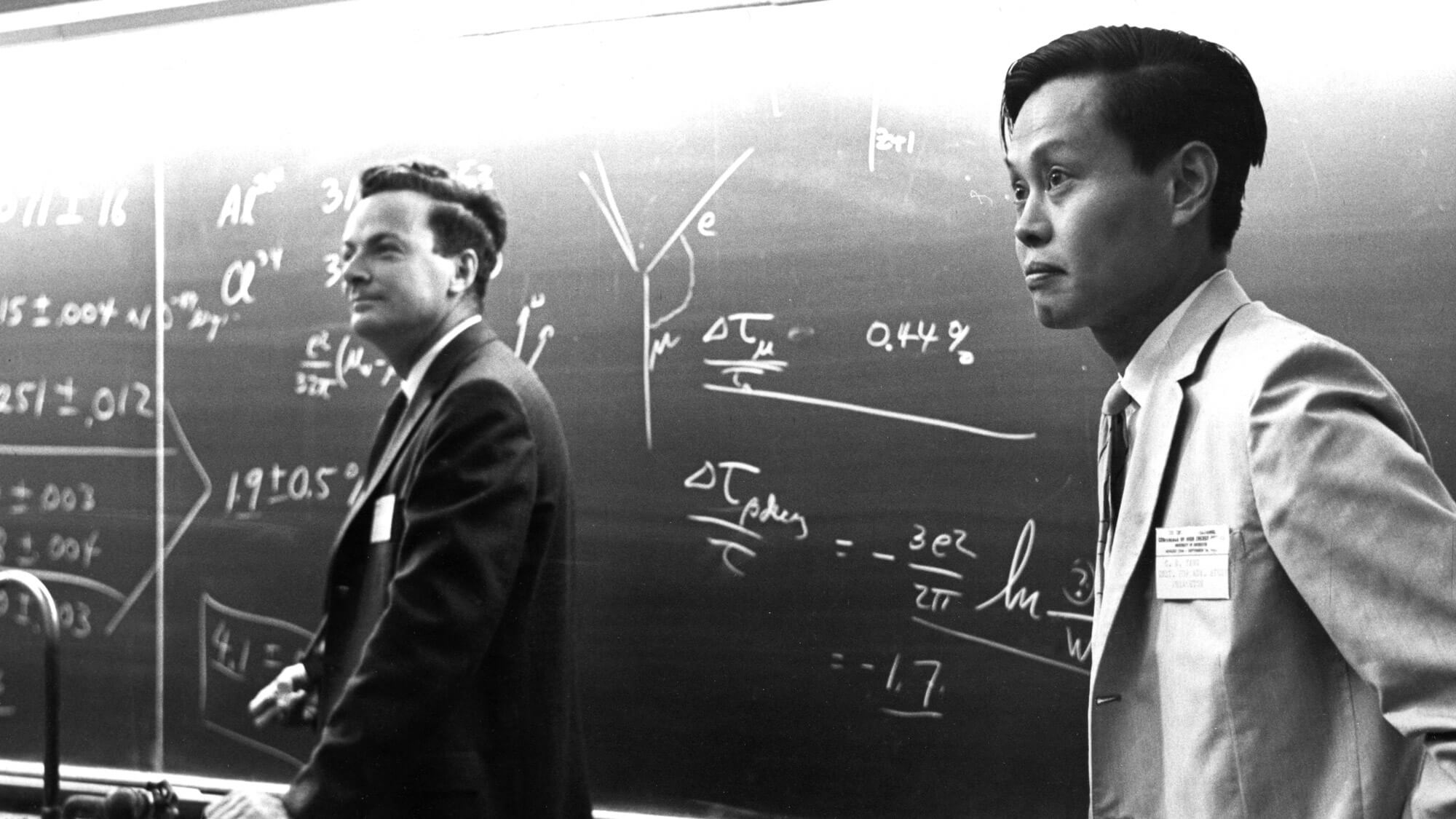

8. We hosted the “who’s who” of physics for many years.

No matter where today’s leading physicists of the world gather for the International Conference on High Energy Physics, many still refer to the gathering as the “Rochester Conference.” Founded by Robert Marshak, who was chair of the University’s physics department for 14 years starting in 1950, the Rochester Conference has long featured a “who’s who” of the physics world. From 1950 to 1957, and then again in 1960, the conference took place in Bausch & Lomb lecture hall 109 with the world’s top physicists such as Nobel Laureates Richard Feynman and Frank C.N. Yang. They even worked on the chalkboard that is still in this very room, which was renovated in 2015

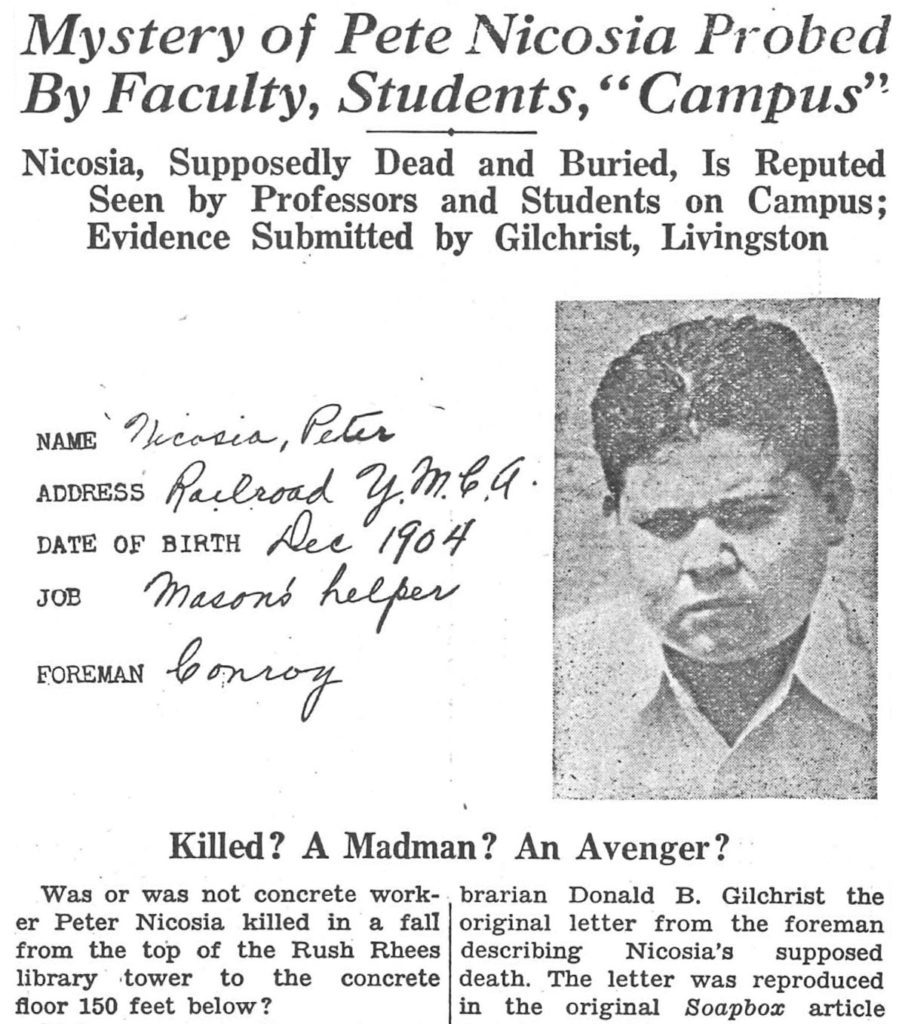

9. Rush Rhees Library may host a ghost.

The legend of Pete Nicosia’s ghost dates back to the building’s construction in the late 1920s. The story goes that Nicosia, a mason’s helper and recent Sicilian émigré, was working on the library tower when he slipped and fell 150 feet to his death. According to Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian, this story is the stuff of Rochester urban legend, a tale probably concocted by Robert F. Metzdorf ’33, ’35 (Mas), ’39 (PhD), a legendary Rochester student and librarian.

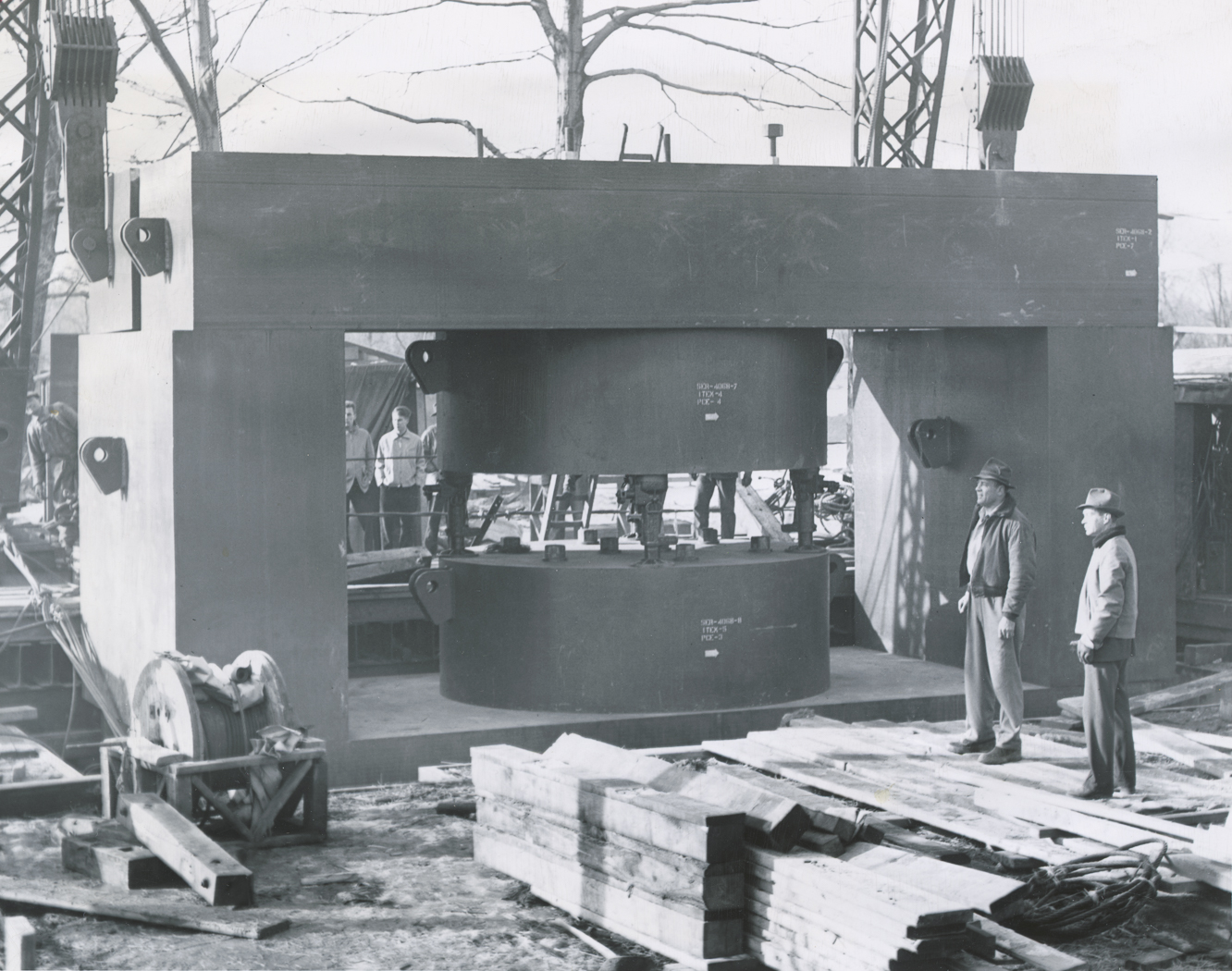

10. Smashing atoms can result in a home for ducks.

The University’s first cyclotron (otherwise known as an atom-smasher) for nuclear research began operation in 1935. A second, larger one, funded primarily by the U.S. Navy Department, was located near where Goergen Hall is today. In turn, it was replaced by a Tandem Van de Graaff accelerator, capable of producing 250 million volts, and operated from 1966–1995.

No story of the cyclotrons is complete without mentioning the duck pond, which was formed from an artesian well to provide cooling water for the atom-smasher. Because of its temperature and purpose, it never froze and provided a safe haven and home for ducks, which first arrived around 1950. The ducks were given a clean bill of health in 1954, after being examined to ensure that the pond water was safe for them.

11. There’s a cave at the Eastman School of Music.

Eastman’s basement has gone by a progression of names. At one time it was formally known as the Basement Assembly. In the 1970s, it was called Fingal’s Cave after the title of a famous orchestral work by Felix Mendelssohn. Today, it’s simply known as the Cave. The word “cave” is actually an apt physical description of the space and the sensation that one gets being down there. It has served various purposes for our students over the decades, including as a gathering place, an Internet café, an eatery, and a place for students to get messages or mail. A very long time ago, it even served as an alternative performance venue.

12. A Morse code message greets visitors outside the Memorial Art Gallery.

In a work entitled “Marking Crossways,” artist Jackie Ferrara cast Morse code symbols into pavers that spell out “The Memorial Art Gallery” and “University of Rochester” as well as colors of the rainbow. The use of Morse code in this way is an artistic nod to the museum’s connection to Western Union, which started as a telegraph company in the mid-1800s and used Morse code to send messages. Emily Sibley Watson, the founder of the museum, came from one of Rochester’s most prominent families. Her father, Hiram Sibley, was a philanthropist, art collector, and co-founder of Western Union with her father-in-law, Don Alonzo Watson.

Explore other areas of the Memorial Art Gallery Sculpture garden here.

Hear the Morse code messages:

—Kristine Thompson, June 2018