Website to help social scientists with research

Website to help social scientists with field research

In 1997, when Gretchen Helmke first starting conducting field research in Buenos Aires, Argentina, something dawned on her pretty quickly. She wasn’t getting anywhere fast.

As a graduate student with no established reputation in the field and little experience, doors didn’t exactly fly open. Studying one of the most politicized institutions in Argentina—the Argentine Supreme Court— she often she didn’t even know which ones to knock on.

“It’s very unusual for a young American woman to go to the Supreme Court and ask them what they’re doing,” says Helmke, who two decades later now chairs the University of Rochester’s political science department.

Scholarly research in the library is one thing. In the field, it’s quite another. As Helmke would soon learn, in a country like Argentina, she first needed to gain access to the right political networks in order for its key members to help open doors for her, point her in the right directions. Even looking the part became important. Her student outfit—jeans, a backpack, and tennis shoes—“just didn’t cut it.”

“To be taken seriously by local elites you need to wear heels, and a suit, carry a bag,” Helmke says. “You need business cards.”

Unlike doing research in the Unites States, which generally offers easy access to government data, trying to so the same in developing nations, can prove tricky.

Helmke got to talking with her former PhD student, Rabia Malik, now a postdoc at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates. Turns out, Malik, faced very similar difficulties.

“Any time I went to a government office in Pakistan, my dad, a former BBC journalist, had to accompany me and introduce himself there first, because without that no one was going to talk to me or respond to my inquiries,” Malik says. Frequently she was told by government officials that the documents she requested were unimportant and that she might want to change the focus of her research.

From left, PhD student YeonKyung Jeong, former PhD student, Rabia Malik, and chair of the University’s political science department Gretchen Helmke are collaborating to create an interactive website designed to help scientists with international field research. (University photo / Sandra Knispel)

Connection with scientists conducting field research

That’s when the two women started brainstorming: what’s the best way to connect with other social scientists on the ground, or those planning to go to the same locale?

The idea of an interactive tool began to take shape in their minds. Helmke, Malik, and current Rochester PhD student YeonKyung Jeong envisioned a website that would track social scientists conducting international field work. On a practical level, being able to glean tips from others means not having to constantly reinvent the wheel.

“Especially when it’s your first field research, you have a very limited amount of information about the field country,” explains Jeong. “You have to spend a lot of time and effort learning about the country, which makes your field research inefficient.”

“Very inefficient,” Helmke adds, laughing. It took her about five months to obtain the Argentine court documents she was tracking down.

“Something like this would have allowed me to ask other scholars basic questions that might have sped up my efforts by months,” Helmke says with 20/20 hindsight.

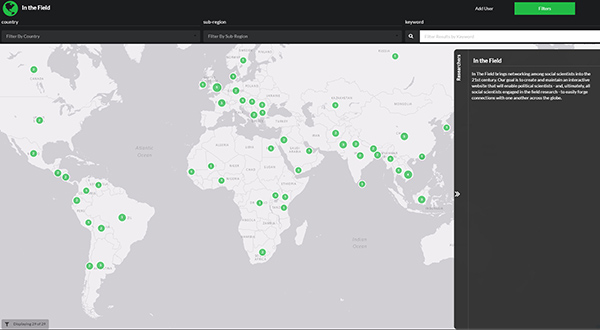

The team recently premiered a beta version of their new website, called In The Field_Political Science, at a conference on the River Campus. Essentially an interactive world map, the website will be searchable by country, city, topic, name of researcher, or institution.

Created with the programming and coding assistance of Nora Dimmock, Blair Tinker, and Josh Romphf of the River Campus Libraries’ Digital Scholarship Lab, the website’s purpose is to foster collaboration among social scientists, make research more efficient, and help advisors plan research trips for graduate students.

A beta version of a new website, called In The Field_Political Science, was featured at a conference on the River Campus this spring. It is slated to go live later this year.

Feedback from other political scientists

Listening to the team’s presentation was Eddy Malesky, a political science professor at Duke University. He laments receiving e-mails that frequently ask similar questions, such as which survey firms to work with in a certain country. Malesky says he’d love to see a list of survey firms listed by country, and rated and ranked by researchers who have worked with them. Users could even include warnings such as “this firm forgot my show cards. This firm, I think, is massaging the data,” Malesky suggests.

Diana Kapiszewski, associate professor in the department of government at Georgetown University, says the site would make it easier to find collaborators, which could increase funding chances. She also suggests including specific country tips and answers to frequently asked questions, written by experts.

Jason Lyall, associate professor of political science at Yale University, hopes Helmke’s team will include pre-research announcements—“So, you don’t get to that country and find someone else is already four or five years deep into the same research.”

Test driving the website

The website is in the pilot stage; the researchers and programmers are still fixing glitches, and are looking for more input from colleagues.

Helmke says the plan is to reach out to faculty and graduate students at several universities in order to populate the website before it goes live. “My guess is we would ultimately have something like 500 to 1,000 users in the political science community, which would expand as we extend to other social sciences.”

Helmke, who has done extensive research in Argentina and Ecuador, hopes to find on the website information that would be useful to her in her role as advisor.

“I feel very comfortable sending students to countries I am familiar with in Latin America, but it is challenging to advise students studying in parts of the world where I have few or no contacts,” she says.

Both Malik and Helmke say they are ready to pass on what they have learned the hard way in the field.

“Don’t lose hope if your emails to Pakistani government offices and politicians go unanswered.” Instead, Malik advises, go and visit them personally. “They’ll be much more receptive.”

Malik also realized something surprising: being underestimated is not necessarily a bad thing.

“Sometimes interviewees will give you more information because they don’t tend to see young female interviewers as aggressive or threatening,” Malik found. “I never consciously tried to come across as quiet or unaggressive, but realized that being polite and passive often meant that I got to hear many more stories about corruption and the like.”

The website is slated to go live later this year. Interested scholars can e-mail Gretchen Helmke with suggestions and questions.

—Sandra Knispel, May 2017